Dev Log

Bolt vs. C# - Thoughts with a dash of rant

It’s not uncommon for me to get asked my thoughts on Bolt (or visual scripting in general) versus using C# in the Unity game engine. It’s a topic that can be very polarizing, leaving some feeling the need to defend their choice or state that their choice is the right one and someone else’s choice is clearly wrong.

Which is better Bolt or C#?

I wouldn’t be writing this if I didn’t have an opinion, but it’s not the same answer for every person. Like most everything, this question has a spectrum of answers and there is no one right answer for everyone at every point in their game development journey. Because that’s what this is no matter whether you are just downloading Unity for the first time, completing your first game, or a senior engineer at a major studio. It’s a journey.

A Little History

Eight years ago I was leaving one teaching job for another and starting to wonder how much longer I would or could stay as a classroom teacher. While doing a little online soul searching, I found an article about learning to code, which had been on my to-do list for a long time, I bookmarked it and came back to the article after starting the new job.

One of the suggestions was to learn to program by learning to use Unity. And I was in love from the moment I made my first terrain and was able to run around on that terrain. I was in love and I continued to play and learn.

It didn’t take long before I needed to do some programming. So I started with Javascript (Unityscript) as it was easy to read and I found a great series of videos walking me through the basics. I didn’t get very far. Coding took a long time and a lot of the code I wrote was a not-so-distant relative to guessing and checking.

Then I saw Playmaker! It looked amazing! Making games without code? Yes. Please! I spend a few months working with Playmaker and I was getting things to work. Very quickly and very easily. Amazing!

But as my projects got more complicated I started to find the limit of the actions built into Playmaker and I got frustrated. Sure I could make a “game” but it’s not a game I wanted to play. As a result, I’d come to the end of my journey with Playmaker.

So I decided to dive into learning C#. I knew it would be hard. I knew it would take time. But I was pretty sure it was what I needed to do next. I struggled like everyone else to piece together tutorials from so many different voices and channels scattered all over YouTube. After a few more months of struggle, I gave in and spent some money.

As a side note that’s a big turning point! That’s when exploring something new starts to turn into a hobby!

I bought a book. And then another and another. I now have thousands of pages of books on Unity, Blender, and C# on my shelves. Each book pushed me further and taught me something new. Years later and I still have books that I need to read.

After a year of starting and restarting new Unity projects, one of those projects started to take shape as an actual game - Fracture the Flag was in the works. But let’s not talk about that piece of shit. I’m very proud to have finished and published it, but it’s wasn’t a good game - no first game ever is. For those who did enjoy the game - thank you for your support!

With an upcoming release on Steam, I felt confident enough to teach a high school course using Unity. Ironically it would be the first of many new courses for me! I choose to use Playmaker over C# for simplicity and to parallel my own journey. No surprise, my students were up and running quickly and having a great time.

But my students eventually found the same limits I did. I would inevitably end up writing custom C# code for my students so they could finish their projects. This is actually how Playmaker is designed to be used, but as a teacher, it’s really hard to see your students limited by the tools you chose for them to use.

That’s when Bolt popped up on my radar! The learning curve was steeper, but it used reflection and that meant almost any 3rd party tool could be integrated AND the majority of the C# commands were ready to use out of the box. Amazing!

I took a chance and committed the class to use Bolt for the upcoming year. As final projects were getting finished most groups didn’t run into the limits of Bolt, but some did. Some groups still needed C# code to make their project work. But that was okay because Bolt 2 was on the horizon and it was going to fix the most major of Bolt’s shortcomings. I still wasn’t using Bolt in my personal projects, but I very much believed that Bolt (and Bolt 2) was the right direction for my class.

Bolt 2 was getting closer and it looked SO GOOD! As a community, we started to get alpha builds to play with and it was, in fact, good - albeit nowhere near ready for production. I started making Bolt 2 videos and was preparing to use Bolt 2 with my students.

And then! Unity bought Bolt and a few weeks later made it free. This meant more users AND more engineers working to improve the tool and finish Bolt 2 faster.

A Fork in the Road

Then higher-ups in Unity decided to cancel Bolt 2. FUCK ME! What?

To be honest, I still can’t believe they did it, but they did. Sometimes I still dream that they’ll reverse course, but I also know that will never happen.

Unity choose accessibility over functionality. Unity choose to onboard more users rather than give current users the tools they were expecting, the tools they had been promised, and the tools they had been asking for.

So what do I mean by that?

For many visual scripting is an easy on-ramp to game development, it’s less intimidating than text-based code and it’s faster to get started with. Plus for some of those without much programming experience, visual scripting may be the easiest or only way to get started with game design.

Now, here’s where I may piss off a bunch of people. That’s not the goal. I’m just trying to honest.

Game development is a journey. We learn as we go. Our skills build and for the first couple of years we simply don’t have the skills to make a complete and polished game that can be solid for profit. In those early days, visual scripting is useful maybe even crucial, but as our projects get more complex current visual scripting tools start to fall apart under the weight of our designs. If you haven’t experienced this yet, that’s okay, but if you keep at game development long enough you will eventually see the shortcomings of visual scripting.

It’s not that visual scripting is bad. It’s not. It’s great for what it is. It just doesn’t have all the tools to build, maintain and expand a project much beyond the prototype stage.

My current project “Where’s My Lunch” is simple, but I wouldn’t dream of creating it with Bolt or any other visual scripting tool.

Bolt 2 was going to bring us classes, scriptable objects, functions, and events - all native to Bolt. While that wasn’t going to bring it on par with C# (still no inheritance or interfaces for starters) it did shore it up enough that (in my opinion) small solo commercial games could be made with it and I could even imagine small indie studios using it in final builds. It was faster, easier to use, and more powerful.

So rather than give the Bolt community the tools to COMPLETE games we have been given a tool to help us learn to use Unity and a tool to help us take those first few steps in our journey of making games.

So What Do I Really Think About Bolt?

Bolt is fantastic. It really is. But it is what it is and not more than that. It is a great tool to get started with game design in Unity. It is, however, not a great tool to build a highly polished game. There are just too many missing pieces and important functionality that doesn’t exist. I don’t even think that adding those features is really Unity’s goal.

Bolt is an onboarding tool. It’s a way to expand the reach and the size of the community using Unity. Unity is a for-profit company and Bolt is a way to increase those profits. That’s not a criticism - it’s just the truth.

Unity has the goal of democratizing game development and while working toward that goal they have been constantly lowering the barrier for entry. They’ve made Unity free and are continuously adding features so that we all can make prettier and more feature-rich games. And Bolt is one more step in that direction.

By lowering the barrier in terms of programming more people will start using Unity. Some of those people will go on to complete a game jam or create an interesting prototype. Some of those people may go on to learn to use Blender, Magica Voxel and C#. And some of those people will go on to make a game that you might one day play.

So yeah, Bolt isn’t the tool that lets you make a game, and it certainly doesn’t allow creating games without code - because that’s just total bullshit - but Bolt is the tool that can help you start on that long journey of making games.

To the Beginner

You should proudly use Bolt. You are learning so much each time you open up Unity. So don’t be embarrassed about using Bolt or other visual scripting tools. Don’t make excuses for it, but do be ready for the day when you need to move on.

You may never make it to that point. You may stay in the stage of making prototypes or doing small game jams and that’s awesome! This journey is really fucking hard. But there may come a day where you have to make the jump to text-based coding. It’s a hard thing to do, but it’s pretty exciting all the same. If and when that day does come don’t forget that Bolt helped you get there and was probably a necessary step in your journey.

To the C# Programmer

If you say visual scripting isn’t coding, then I’m pretty sure by that logic digital art isn’t art because it’s not done “by hand.” Text doesn’t make it coding. Just like using assembly language isn’t required to be a programmer.

Even if you don’t use visual scripting you can probably read it and help others. It’s okay to nudge folks in the direction of text-based coding. It is after all a more complete tool, but don’t be a jerk about it or make people feel like they are wasting their time. You aren’t superior just because you started coding earlier, had a parent that taught you to program, or were lucky enough to study computer science in college. Instead, I think you have a duty to support those who are getting started just like you did many years ago.

To the Bolt Engineers

Ha! Imagine that you are actually reading this.

I know you work hard. I know you are doing your best. I know you are doing good things. Keep it up. You are helping to get more people into game development and that is a good thing for all of us.

One small request? Please put your weekly work log in a separate discord channel so we can see them all together or catch up if we miss a few. The Chat channel seems like one of the worst places to put those posts.

To Unity Management

I’m glad you’ve realized that Unity was a poop show and you are doing your best to fix it. It’s a long process and we expect good things in the future.

BUT! I think you made a mistake with Bolt 2 and you let the larger Bolt community down. It was that same community that helped build Bolt into an asset you wanted to buy. You told us one thing and you did another. You made a promise and you broke it. Just look at the Bolt discord a year ago vs. now. It’s a very different community and those who built it have largely disappeared.

Stop selling Bolt as a complete programming tool. And seriously! There is no video game development without coding. That’s a fucking lie and you know it. If you don’t? That’s a bigger problem.

I am sure that you will make more money with Bolt integrated into Unity than if Bolt 2 had continued. That’s okay. Just don’t pretend that wasn’t a huge piece of the motivation. Be honest with your community. Bolt and other visual scripting tools are stepping stones. It’s part of a larger journey. It’s not complicated. It’s not demeaning. It’s just the truth. We can handle the truth. Can you?

To the YouTuber

If your title or thumbnail for a Bolt video contains the words “without Code” you are doing that for clicks and views. It’s not serving your audience and it’s not helping them make games. You are playing a game (the YT game). So please stop.

Coroutines - Unity & C#

Do you need to change a value over a few frames? Do you have code that you’d like to run over a set period of time? Or maybe you have a time-consuming process that if run over several frames would make for a better player experience?

Like almost all things there is more than one way to do it, but one of the best and easiest ways to run code or change a value over several frames is to use a coroutine!

But What Is A Coroutine?

Coroutines in many ways can be thought of as a regular function but with a return type of “IEnumerator.” While coroutines can be called just like a normal function, to get the most out of them, we need to use “StartCoroutine” to invoke them.

But what is really different and new with coroutines (and what also allows us to leverage the power of coroutines) is that they require at least one “yield” statement in the body of the coroutine. These yield statements are what give us control of timing and allow the code to be run asynchronously.

It’s worth noting that coroutines are unique to Unity and are not available outside of the game engine. The yield keyword, IEnumerable interface, and the IEnumerator type are however native to C#.

But before we dig in too deep, let’s get one misconception out of the way. Coroutines are not multi-threaded! They are asynchronous multi-tasking but not multi-threaded. C#does offer async functions, which can be multi-threaded, but those are more complex and I’m hopeful it will be the topic of a future video and blog post. If async functions aren’t enough you can go to full-fledged multi-threading, but Unity is not thread-safe and this gets even more complex to implement.

Changing a Numeric Value - Update or Coroutine?

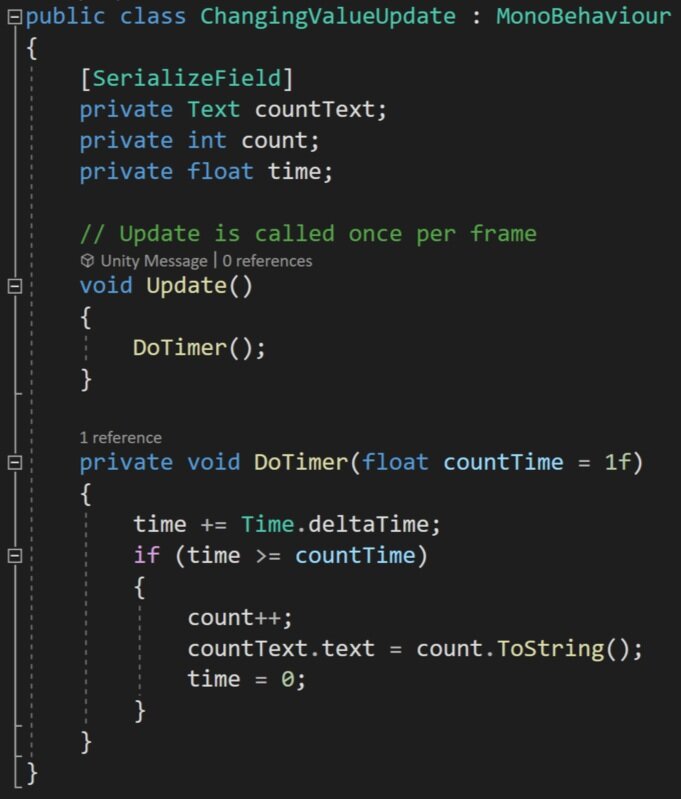

Update method… Not so awesome

So let’s start with a simple example of changing a numeric value over time. To make it easier to see the results, let’s display that value in a UI text element.

We can of course do this with the standard update function and some type of timer, but the implementation isn’t particularly pretty. I’ve got three fields, an if statement, and an update that is going to run every frame that this object is turned on.

While this works, there is a better and cleaner way. Which of course is a coroutine.

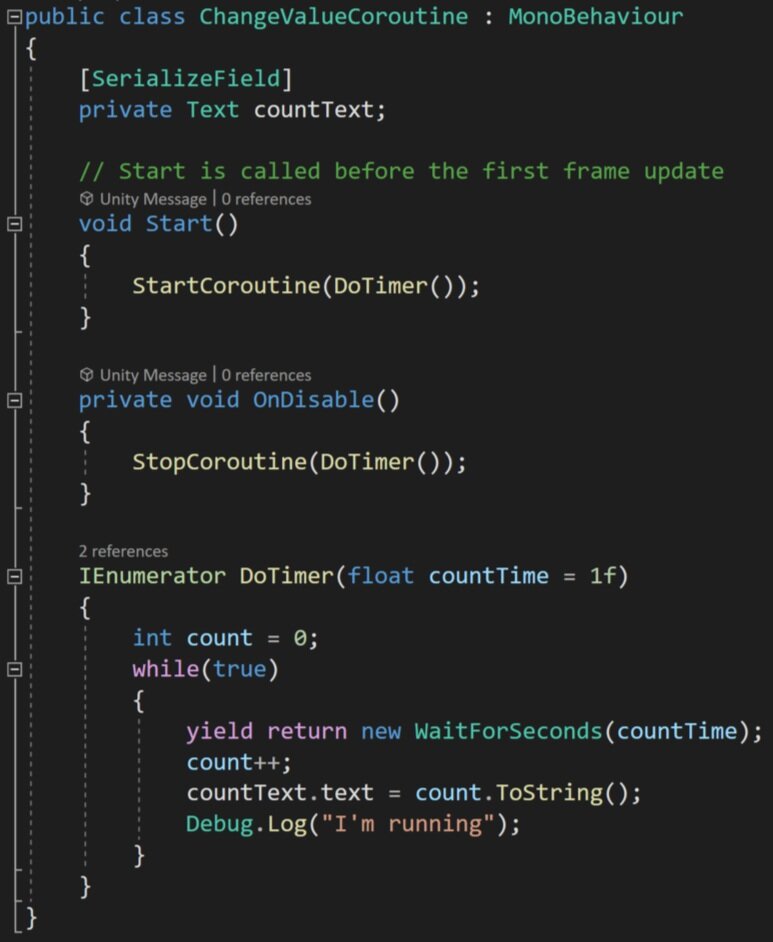

Corountines are much Cleaner

So let’s look at a coroutine that has the same result as the update function. We can see the return type of the coroutine is an IEnumerator. Notice that we can include input parameters and default values for those parameters - just like a regular function. Then inside the coroutine, we can define the count which will be displayed in the text. This variable will live as long as the coroutine is running, so we don’t need a class-wide variable making things a bit cleaner.

And despite personally being scared of using while statements this is a good use of one. Inside the while loop, we encounter our first yield statement. Here we are simply asking the computer to yield and wait for a given number of seconds. This means that the computer will return to the code block that started the coroutine as if the coroutine had been completed and continue running the rest of the program. This is an important detail as some users may expect the calling function to also pause or wait.

THEN! When wait time is up the thread will return to the coroutine and run until it terminates or in this case loops through and encounters another yield statement.

The result, I would argue while not shorter is much cleaner than an update function. Plus the coroutine only runs once per second vs. once per frame and as a result, it will be more performant.

In my personal projects, I’ve replaced update functions with coroutines for functionality that needed to run consistently but not every frame - and it made a dramatic improvement in the performance of the game.

As mentioned earlier, to invoke the coroutine we need to use the command “StartCoroutine.” This function has 2 main overloads. One that takes in a string and the second which takes in the coroutine itself. The string-based method can not take in input parameters and I generally avoid the use of strings, if possible, so I’d recommend the strongly typed overload.

Stopping a Coroutine

If you have a coroutine, especially one that doesn’t automatically terminate, you might also want to stop that coroutine when it’s no longer needed or if some other event occurs and you want to stop the process of the coroutine.

Unlike an update function if the component is turned off the coroutine will not automatically stop. But! If the gameObject with the coroutine is turned off or destroyed the coroutine will stop.

So that’s one way and can certainly work for some applications. But what if you want more control?

You can bring down the hammer and use “StopAllCoroutines” which stops all the coroutines associated with the given component.

Stop a particular coroutine by reference

Personally, I’ve often found this sufficient, but you can also stop individual coroutines with the function “StopCoroutine” and give it a reference to the particular coroutine that you want to stop. This is done by telling it explicitly which coroutine by name OR I recently learned you can cache a reference to a coroutine and use that reference in the stop coroutine function. This method is useful if there is more than one coroutine running at a time - we’ll look at an example of that later.

If you want to ensure that a coroutine stops when a component is disabled, you can call either call stop coroutine or stop all coroutines from an “OnDisable” function.

It’s also worth noting that you can get more than one instance of a coroutine running at a time. This could happen if a coroutine is started in an update function or a while loop. This can cause problems especially if that coroutine, like the one above, never terminates and could quickly kill performance.

A Few Other Examples

Other uses of coroutines could be simple animations. Such as laying down the tiles of a game board. Using a coroutine may be easier to implement and quicker to adjust than a traditional animation.

The game board effect, shown to the right, actually makes use of two coroutines. The first instantiates a tile in a grid and waits a small amount of time before instantiating the next tile.

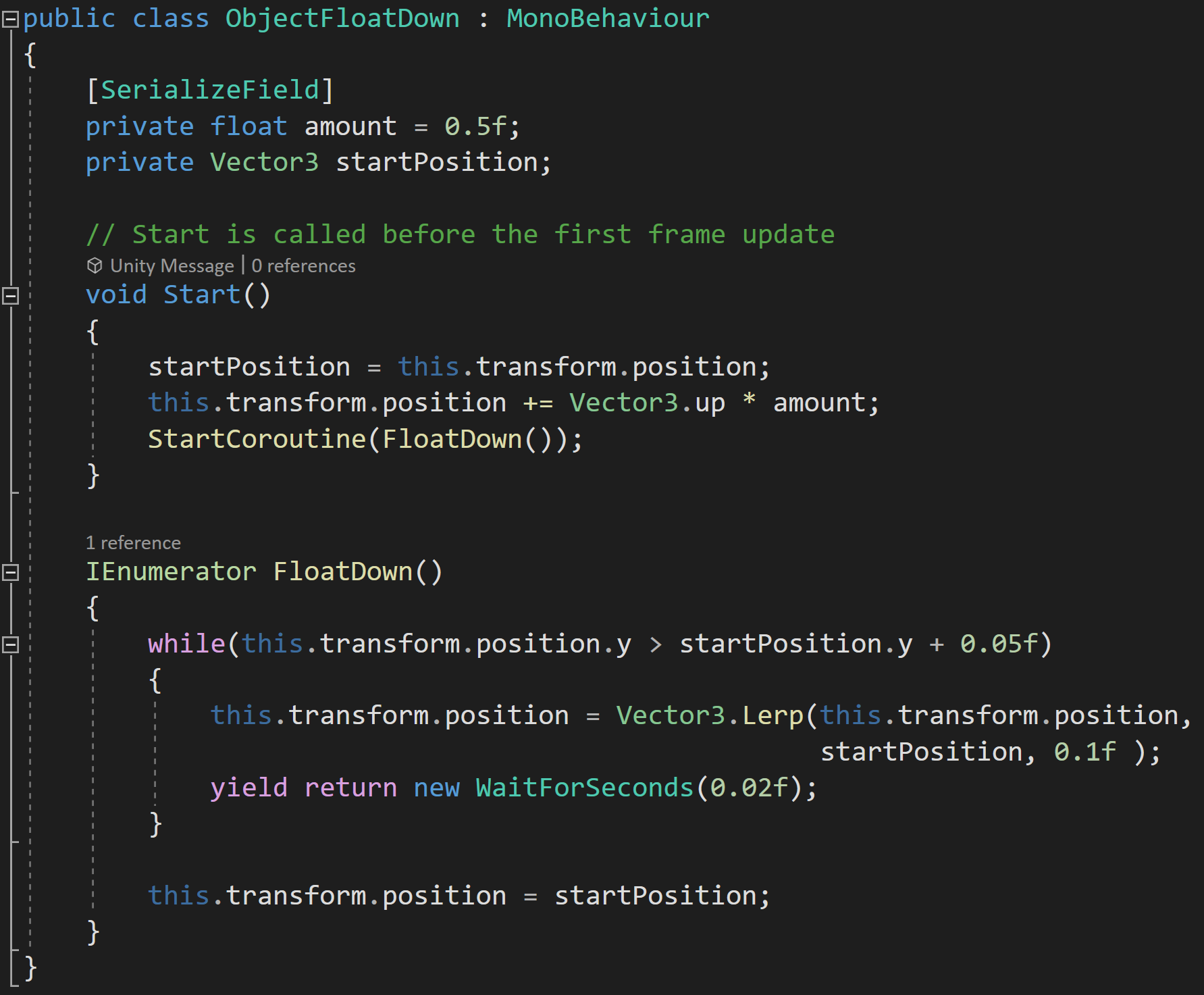

The second coroutine is run from a component on each tile. This component caches the start location then moves the object a set amount directly upward and then over several frames lerps the object’s position back to the original or intended position. The result is a floating down-like effect.

Another advantage of using a coroutine over a traditional animation is the reusability of the code. The coroutine can easily be added to any other game object with the parameters of the effect easily modified by adjusting the values in the inspector.

Instantiate the Board Tiles

Make those Tiles float down into position

Notice that in the float down code it doesn’t wait for the position to get back to the original location since a lerp will never get to the final value. So if the coroutine ran the while loop until it got to the exact original position the coroutine would never terminate. If the exact position is important the position can be set after exiting the while loop.

Caching and Stopping Coroutines

Coroutines can also be used to easily create smooth movement such as a game piece moving around the board.

But there is a potential snag with this approach. In my case, I’m using a lerp function to calculate where the game piece should move to for the next frame. The problem comes when using a lerp function that operates over several frames. This creates the smooth motion - but in that time the player could click on a different location, which would start another instance of the coroutine, and then both coroutines would be trying to move the game piece to different locations and neither would ever be successful or ever terminate.

This is a waste of resources, but worse than that the player will lose control and not be able to move the game piece.

A simple way to avoid this issue is to cache a reference to the coroutine. This is made easy, as the start coroutine function returns a reference to the started coroutine!

Then all we need to do, before starting a new coroutine is to check if the coroutine variable is null, if it’s not we can stop the previous coroutine before starting the next coroutine.

It’s easy to lose control or lose track of coroutines and caching references is a great way to maintain that control.

Yield Instructions!

The yield instructions are the key addition to coroutines vs. regular functions and there are several options built into Unity. It is possible to create your own custom yield instructions and Unity provides some documentation on how to do that if your project needs a custom implementation.

Maybe the most common yield instruction is “wait for seconds” which pauses the coroutine for a set number of seconds before returning to execute the code. If you are concerned about garbage collection and are using “wait for seconds” frequently with the same amount of time you can create an instance of it in your class. This is useful if you’ve replaced some of your update functions with coroutines and that coroutine will be called frequently while the game is running.

Another common yield statement is to return “null.” This causes Unity to wait until the next frame to continue the corountine which is particularly useful if you want an action to take place overall several frames - such as a simple animation. I’ve used this for computationally heavy tasks that could cause a lag spike if done in one frame. In those cases, I simply converted the function to a coroutine and sprinkled in a few yield return null statements to break it up over several frames.

An equally useful, but I think often forgotten yield statement is “break” which simply ends the execution of a coroutine much like the “return” command does in a traditional function.

“Wait Until” and “Wait While” are similar in function in that they will pause the coroutine until a delegate evaluates as true or while a delegate is true. These could be used to wait a specific number of frames, wait for the player score to equal a given value, or maybe show some dialogue when a player has died three times.

“Wait For End of Frame” is a great way to ensure that the rest of the game code for that frame has completed as well as after cameras and GUI have rendered. Since it is often hard, or impossible, to control what code executes before other code this can be very useful if you need specific code to run after other code is complete.

“Wait for Fixed Update” is pretty self-explanatory and waits for “fixed update” to be called. Unity doesn’t specify if this triggers before, after, or somewhere in the in-between when fixed update functions are getting called.

Wait for “Seconds Real-Time” is very similar to “wait for seconds” but as the name suggests it is done in real-time and is not affected by the scaling of time whereas “wait for seconds” is affected by scaled time.

Other Bits and Details

Many when they get started with Unity and coroutines think that coroutines are multi-threaded but they aren’t. Coroutines are a simple way to multi-task but all the work is still done on the main thread. Mult-threading in Unity is possible with async function or manually managing threads but those are more complex approaches. Multi-tasking with coroutines means the thread can bounce back and forth between tasks before those tasks are complete, but can’t truly do more than one task at once.

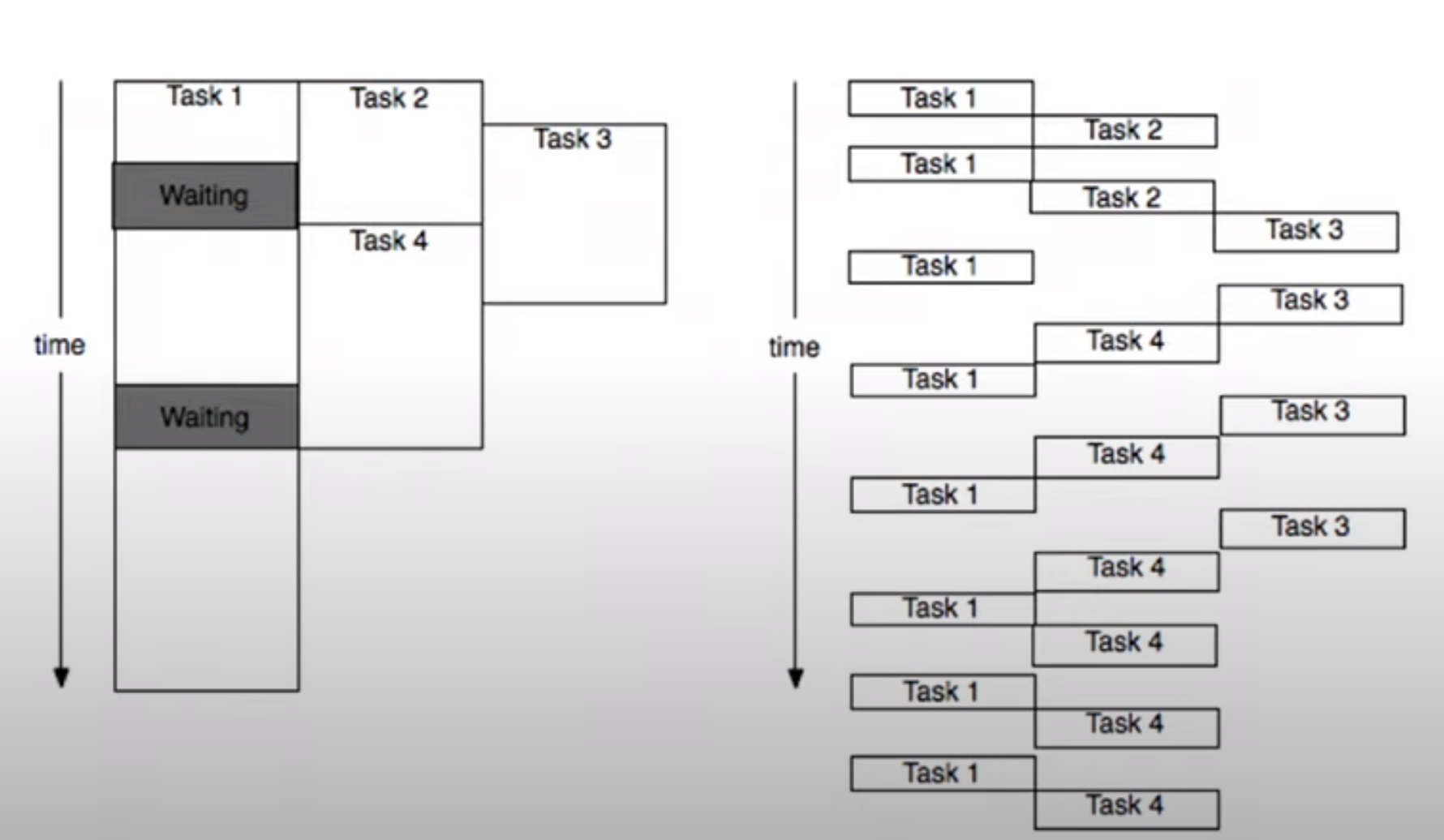

The diagram to the right is stolen from the video Best Practices: Coroutines vs. Async and is is a great visual of real multi-threading on the left and what multi-tasking with coroutines actually does.

While pretty dry, the video does offer some very good information and some more detailed specifics on coroutines.

It’s also worth noting that coroutines do not support return values. If you need to get a value out of the coroutine you’ll need a class-wide variable or some other data structure to save and access the value.

Where's My Lunch? - January Devlog Update

Six months ago the game “Where’s My Lunch?” was born out of the Game Makers Toolkit GameJam. The original game idea was to use bombs to move the player object around the scene to some sort of goal - trying to play on the jam’s theme of “Out of Control.” Nothing too clever, but physics and explosions are generally good fun and it seemed like a good starting point.

Every game or project I’d ever made in Unity was 3D and WML was no different. It started as a 3D game with the simple colored cubes and spheres standing pretending to be game art. It was clumsy and basic but still, it felt like it had some potential.

That first evening, I started to work on the art style. I needed something simple, quick, and hopefully not too hard to look at… After bumping around with a few ideas, I downloaded FireAlpaca and starting drawing stick figures. For the life of me, I can’t remember why… I just did. I tossed on a hat to add a little character and Hank was born and I was on my way to making my first ever 2D game!

Early 3d Prototype

With great input from viewers as I streamed the game’s progress, I added gravity wells and portals to the project to add even more physics-based chaos to the game. With the help of a clumsy but effective save system, I created a dozen playable levels. I was even able to add a sandbox level which was another suggestion from a viewer.

With time running out on the 48 hour game jam, I did my best to fix a few bugs, pushed a build to Itch, and submitted my efforts to the game jam. I’d spent somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 hours working on the game and I was pretty content with the results.

The game finished in the top 10% of over 5000 games submitted, which while we always dream higher, I have to admit felt pretty darn good. With the results posted, I mentally closed up the project and didn’t intend to come back to it. I’d learned a lot and had some fun. What more was there to do with the game?

Where’s My Lunch?

I still dream of Making this game

Like so many others I’ve had projects come and go. With most not getting finished due to over scoped game ideas and lack of time to make those ideas a reality. This is a lesson I continue to struggle to learn…

A few months after the game jam, the idea came along to polish and publish a small game while making video content along the way. I loved it! It seemed like a perfect project.

I spent much of October and November planning out the project with an eye to keeping the scope small but still adding ideas and topics that might make useful videos and hopefully a more engaging game. I started work on a notion page (which I much prefer to Trello) trying to find the balance between tasks that were too big or too small. And to be honest, I’ve never forced myself to fully plan out a game to this level of detail.

The planning wasn’t particularly fun, I had to actively fight the urge to open Unity and just get to work… I didn’t list absolutely everything that needed to be done, but I got most of it and I think the result was more than worth the effort.

I knew the scope of the game. I knew what I needed to do next. And in some way, I had a contract with myself as to what I was making with clear limits on the project.

All of this had me hopeful that the project will have a different ending than so many of my past projects.

Progress?

With the planning was done it was time for the fun part. Digging into the code!

Most of the early hours spent with the code didn’t make a big difference in the appearance or even the player experience. Much of that early time was spent shoring up the underlying framework, making code more generic and more robust. I wanted to be able to add mechanics and features without breaking the game with each addition. Yes, we’ve all been there. While maybe not the highest standard, I’ve come to judge my own work by what needs to happen to add a new feature, how long that takes, and how much else breaks in the process.

Does adding a new level to the game require rewriting game manager code? Or manually adding a new UI button? Or can I simply add a game level object to a list and the game handles the rest?

What about adding the ability to change the color of an object when the player selects it? Does that break the placement system? Does that result in messy code that will need to be modified for each new game item? Or can it be done by creating a simple, clean and easy to use component that can be added to any and all selectable objects?

Holding myself to this standard and working in a small scoped game has felt really good. It hasn’t always been easy AND importantly I don’t think I could have held myself to that standard during the game jam. There simply wasn’t time.

For example, during the game jam I wanted players to be able to place the portals to solve a level but in order for a portal to work it needs to have a connection to another portal… The simplest solution was to create a prefab that was a parent object with two children portals. This meant when they were added they could already be connected. And while this worked it also created all kinds of messy code to handle this structure. Which meant I had all these “if the object is a portal then do this” statements throughout the code. For me, those lines were red flags that the code wasn’t clean and it was going to need some work.

Fixing that was no small task. Every other game item was a single independent object. Plus, I knew that I wanted to have other objects that could connect like a lever and a gate or a lever and a fan and the last thing I wanted to do was add a bunch more one-off if statements to handle all those special cases.

Player made connections in Orange

My solution was to break the portals down into single unconnected objects and to allow the player to make connections by “drawing” the connection from one portal to another portal. I really like the results, especially in a hand-drawn game, but man, did it cause headaches and break a poop ton of code in the process.

Connecting portals functionally was pretty easy, drawing the lines wasn’t too hard, but updating the lines when one portal is moved or saving and then loading that hand-drawn line… Big ugh!

But! It works.

AND!

The framework doesn’t just work for portals it works for any object. Simply change the number of allowed connections in the inspector for a given prefab and it works! Adding the lever and gate objects required ZERO extra code in the connection system! The fan? Yep. No problem. Piece of cake.

Simply. Fucking. Amazing.

Vertical Slice?

To be honest, I’ve never fully understood the idea of a vertical slice of a game. Maybe that was because my games were too complex and I never got there? I don’t know, but a couple of months ago, it clicked. I understood the idea and why you would make a vertical slice.

Then I heard someone else describe it… And I was back to not being so sure.

So here’s my definition. Maybe it’s right. Maybe it’s not. I’m not sure I actually care because what I did made sense to me, it worked and I’d do it again. To me, a vertical slice means getting all the systems working. Making them general. Making them ready to handle more content. Making them robust and flexible.

For Where’s My Lunch that meant getting the save and load system working, debugging the placement system, making the UI adapt to new game elements without manual work, implementing Steamworks, adding Steam workshop functionality, and a bunch of other bits that I’ve probably forgotten about.

To me, a vertical slice means I can add mechanics and features without breaking the game and those additions are handled gracefully and as automated as possible.

Adding Content

My to-Do List with game content towards the bottom

Maybe it’s surprising, but adding new mechanics is pretty low on my to-do list. As I start to reflect on this project as a whole, this may be one of the bigger things I’ve learned. About the only items lower are tasks such as finalizing the Steam Store, creating a trailer and adding trading cards. Things that rely on adding more content to the game.

So, with the “vertical slice” looking good, I quickly added several new game items that weren’t part of the game jam version. Speed zones, levers, gates, fans, spikes, and balloons with a handful more still on the to-do list. Each game item took two or three hours including the art, building the prefab, and writing the mechanics specific code. Each item gets added to the game by simply dropping in the prefab to a list on a game manager and making sure there is a corresponding value or type of an enum that is used to identify and handle the objects by other classes.

And that is so satisfying!

100% I will revisit and tweak these new objects, but they work! And they didn’t break anything when I added them.

Simply. Fucking. Amazing.

What’s Next?

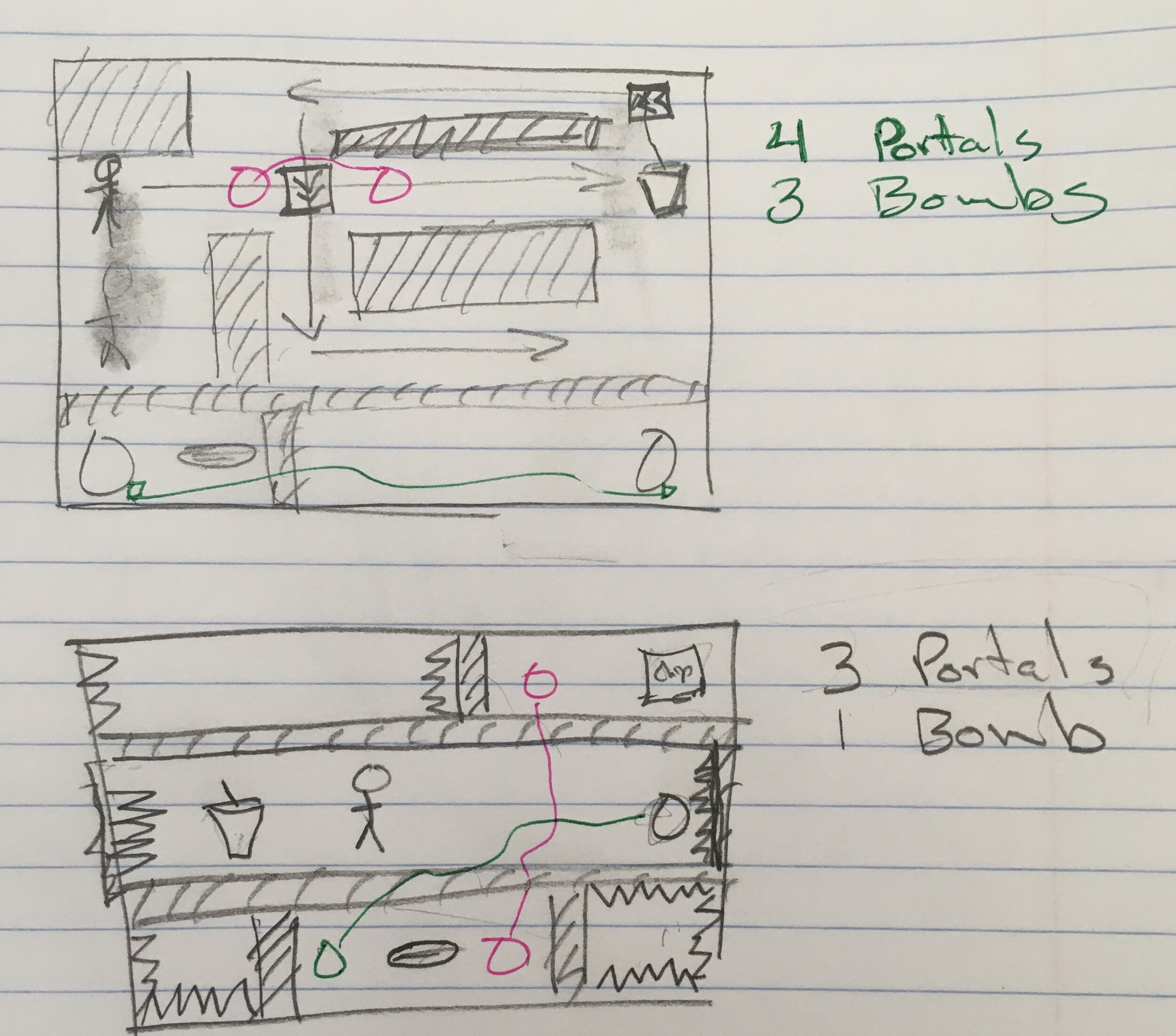

Analog Level Planning

The hardest part! Designing new levels.

The plan from here on out is to use the level designer that’s built into the game - that level that started as a sandbox playground.

To help make that process easier I’ve added box selection, copy and paste, (very) basic undo functionality, and a handful of other quality of life improvements. My hope is that players will be inspired to create and share levels and the easier those levels are to create the more levels they’ll create.

I also want to add enough levels to keep players busy for a good while. How long? I don’t know. It’s scary to think about how many levels I might need for an hour or two hours or five hours of gameplay…

While the framework is in place and gets more and more bug-free each day, there is still a lot of work to do and a lot that needs to be created.

Older Posts

-

January 2026

- Jan 27, 2026 Save and Load Framework Jan 27, 2026

-

April 2024

- Apr 10, 2024 Ready for Steam Next Fest? - Polishing a Steam Page Apr 10, 2024

- Apr 1, 2024 Splitting Vertices - Hard Edges for Low Poly Procedural Generation Apr 1, 2024

-

November 2023

- Nov 18, 2023 Minute 5 to Minute 10 - Completing the Game Loop Nov 18, 2023

-

September 2023

- Sep 13, 2023 Visual Debugging with Gizmos Sep 13, 2023

-

July 2023

- Jul 4, 2023 Easy Mode - Unity's New Input System Jul 4, 2023

-

May 2023

- May 19, 2023 Level Builder - From Pixels to Playable Level May 19, 2023

-

April 2023

- Apr 11, 2023 Input Action in the Inspector - New Input System Apr 11, 2023

-

February 2023

- Feb 26, 2023 Tutorial Hell - Why You're There. How to Get Out. Feb 26, 2023

-

December 2022

- Dec 31, 2022 Upgrade System (Stats Part 2) Dec 31, 2022

-

November 2022

- Nov 10, 2022 Stats in Unity - The Way I Do it Nov 10, 2022

- Nov 5, 2022 State of UI in Unity - UI Toolkit Nov 5, 2022

-

August 2022

- Aug 17, 2022 Knowing When A Coroutine Finishes Aug 17, 2022

-

April 2022

- Apr 23, 2022 Unity Input Event Handlers - Or Adding Juice the Easy Way Apr 23, 2022

-

March 2022

- Mar 15, 2022 *Quitting a Job I Love Mar 15, 2022

-

February 2022

- Feb 8, 2022 Split Screen: New Input System & Cinemachine Feb 8, 2022

-

January 2022

- Jan 24, 2022 (Better) Object Pooling Jan 24, 2022

- Jan 19, 2022 Designing a New Game - My Process Jan 19, 2022

- Jan 16, 2022 Strategy Game Camera: Unity's New Input System Jan 16, 2022

-

December 2021

- Dec 16, 2021 Raycasting - It's mighty useful Dec 16, 2021

-

November 2021

- Nov 22, 2021 Cinemachine. If you’re not. You should. Nov 22, 2021

-

August 2021

- Aug 3, 2021 C# Extension Methods Aug 3, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 27, 2021 Changing Action Maps with Unity's "New" Input System Jun 27, 2021

-

May 2021

- May 28, 2021 Unity's New Input System May 28, 2021

- May 8, 2021 Bolt vs. C# - Thoughts with a dash of rant May 8, 2021

-

March 2021

- Mar 10, 2021 Coroutines - Unity & C# Mar 10, 2021

-

January 2021

- Jan 14, 2021 Where's My Lunch? - January Devlog Update Jan 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 27, 2020 C# Generics and Unity Dec 27, 2020

- Dec 7, 2020 Steam Workshop with Unity and Facepunch Steamworks Dec 7, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 27, 2020 Simple Level Save and Load System (Unity Editor) Nov 27, 2020

- Nov 9, 2020 Command Pattern - Encapsulation, Undo and Redo Nov 9, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 28, 2020 GJTS - Adding Steamworks API and Uploading Oct 28, 2020

- Oct 9, 2020 Game Jam... Now What? Oct 9, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 16, 2020 Strategy Pattern - Composition over Inheritance Aug 16, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 24, 2020 Observer Pattern - C# Events Jul 24, 2020

- Jul 15, 2020 Object Pooling Jul 15, 2020

- Jul 3, 2020 Cheat Codes with Unity and C# Jul 3, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 16, 2020 The State Pattern Jun 16, 2020

-

August 2019

- Aug 12, 2019 Easy UI Styles for Unity Aug 12, 2019

-

July 2019

- Jul 3, 2019 9th Grade Math to the Rescue Jul 3, 2019

-

June 2019

- Jun 12, 2019 Introducing My Next Game (Video DevLog) Jun 12, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 29, 2019 Programming Challenges May 29, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 2, 2019 Something New - Asking "What Can I Learn?" Mar 2, 2019

-

November 2018

- Nov 30, 2018 A Growing Channel and a New Tutorial Series Nov 30, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 11, 2018 Procedural Spaceship Generator Oct 11, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 11, 2018 Implementing SFX in Unity Jul 11, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 31, 2018 Prototyping Something New May 31, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 17, 2018 When to Shelve a Game Project? Apr 17, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 9, 2018 State of the Game - Episode 3 Feb 9, 2018

-

December 2017

- Dec 16, 2017 State of the Game - Episode 2 Dec 16, 2017

-

November 2017

- Nov 7, 2017 The Bump From A "Viral" Post Nov 7, 2017

-

October 2017

- Oct 30, 2017 NPC Job System Oct 30, 2017

-

September 2017

- Sep 1, 2017 Resources and Resource Systems Sep 1, 2017

-

August 2017

- Aug 3, 2017 State of the Game - Episode 1 Aug 3, 2017

-

June 2017

- Jun 20, 2017 Resources: Processing, Consumption and Inventory Jun 20, 2017

- Jun 15, 2017 Energy is Everything Jun 15, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 16, 2017 Graphing Script - It's not exciting, but it needed to be made May 16, 2017

- May 2, 2017 Tutorials: Low Poly Snow Shader May 2, 2017

-

April 2017

- Apr 28, 2017 Low Poly Snow Shader Apr 28, 2017

- Apr 21, 2017 Environmental Simulation Part 2 Apr 21, 2017

- Apr 11, 2017 Environmental Simulation Part 1 Apr 11, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 24, 2017 Building a Farming Game Loop and Troubles with Ground Water Mar 24, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 25, 2017 The Inevitable : FTF PostMortem Feb 25, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 7, 2016 Leaving Early Access Dec 7, 2016

-

November 2016

- Nov 28, 2016 Low Poly Renders Nov 28, 2016

- Nov 1, 2016 FTF: Testing New Features Nov 1, 2016

-

October 2016

- Oct 27, 2016 Watchtowers - Predictive Targeting Oct 27, 2016

- Oct 21, 2016 Click to Color Oct 21, 2016

- Oct 19, 2016 Unity Object Swapper Oct 19, 2016

-

September 2016

- Sep 18, 2016 Testing Single Player Combat Sep 18, 2016

-

May 2016

- May 25, 2016 Release Date and First Video Review May 25, 2016

-

March 2016

- Mar 26, 2016 Getting Greenlit on Steam Mar 26, 2016