Dev Log

Strategy Game Camera: Unity's New Input System

I was working on a prototype for a potential new project and I needed a camera controller. I was also using Unity’s “new” input system. And I thought, hey, that could be a good tutorial…

There’s also a written post on the New Input System. Check the navigation to the right.

The goal here is to build a camera controller that could be used in a wide variety of strategy games. And to do it using Unity’s “New” Input System.

The camera controller will include:

Horizontal motion

Rotation

Zoom/elevate mechanic

Dragging the world with the mouse

Moving when the mouse is near the screen edge

Since I’ll be using the New Input System, you’ll want to be familiar with that before diving too deep into this camera controller. Check either the video or the written blog post.

If you’re just here for the code or want to copy and paste, you can get the code along with the Input Action Asset on GitHub.

Build the Rig

Camera rig Hierarchy

The first step to getting the camera working is to build the camera rig. For my purposes, I choose to keep it simple with an empty base object that will translate and rotate in the horizontal plane plus a child camera object that will move vertically while also zooming in and out.

I’d also recommend adding in something like a sphere or cube (remove its collider) at the same position as the empty base object. This gives us an idea of what the camera can see and how and where to position the camera object. It’s just easy debugging and once you’re happy with the camera you can delete the extra object.

Camera object transform settings

For my setup, my base object is positioned on the origin with no rotation or scaling. I’ve placed the camera object at (0, 8.3, -8.8) with no rotation (we’ll have the camera “look at” the target in the code).

For your project, you’ll want to play with the location to help tune the feel of your camera.

Input Settings

Input Action Asset for the Camera Controller

For the camera controller, I used a mix of events and directly polling inputs. Sometimes one is easier to use than another. For many of these inputs, I defined them in an Input Action Asset. For some mouse events, I simply polled the buttons directly. If that doesn’t make sense hopefully it will.

In the Input Action Asset, I created an action map for the camera and three actions - movement, rotate, and elevate. For the movement action I created two bindings to allow the WASD keys and arrows keys to be used. It’s easy, so why not? Also important, both rotate and elevate have their action type set to Vector2.

Importantly the rotate action is using the delta of the mouse position not the actual position. This allows for smooth movement and avoids the camera snapping around in a weird way.

We’ll be making use of the C# events. So make sure to save or have auto-save enabled. We also need to generate the C# code. To do this select the Input Action Asset in your project folders and then in the inspector click the “generate C# class” toggle and press apply.

Variables and More Variables!

Next, we need to create a camera controller script and attach it to the base object of our camera rig. Then inside of a camera controller class we need to create our variables. And there’s a poop ton of them.

The first two variables will be used to cache references for use with the input system.

The camera transform variable will cache a reference to the transform with the camera object - as opposed to the empty object that this class will be attached to.

All of the variables with the BoxGroup attribute will be used to tune the motion of the camera. Rather than going through them one by one… I’m hoping the name of the group and the name of the variable clarifies their approximate purpose.

The camera settings I’m using

The last four variables are all used to track various values between functions. Meaning one function might change a value and a second function will make use of that value. None of these need to have their value set outside of the class.

A couple of other bits: Notice that I’ve also added the UnityEngine.InputSystem namespace. Also, I’m using Odin Inspector to make my inspector a bit prettier and keep it organized. If you don’t have Odin, you should, but you can just delete or ignore the BoxGroup attributes.

Horizontal Motion

I’m going to try and build the controller in chunks with each chunk adding a new mechanic or piece of functionality. This also (roughly) means you can add or not add any of the chunks and the camera controller won’t break.

The first chunk is horizontal motion. It’s also the piece that takes the most setup… So bear with me.

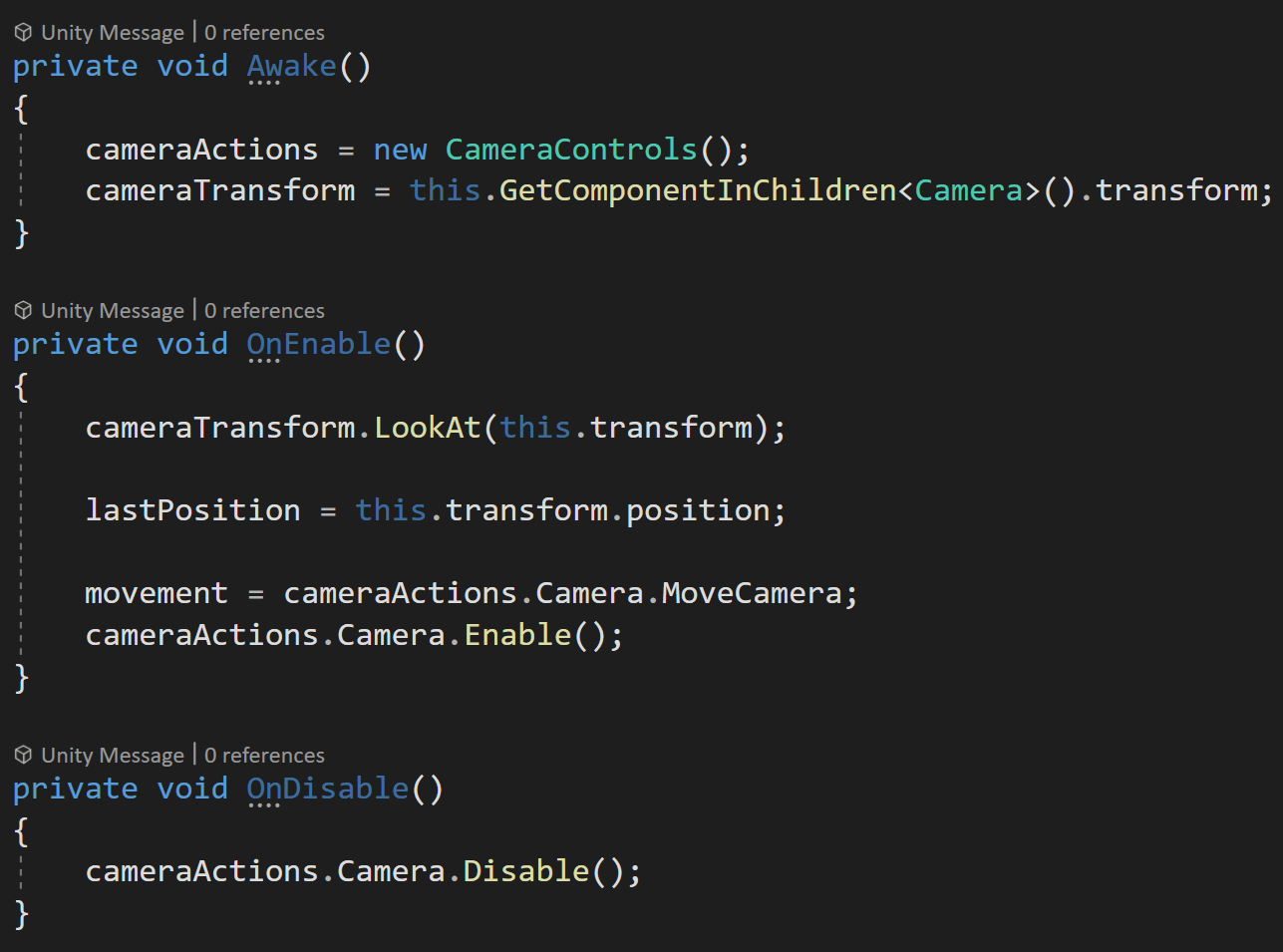

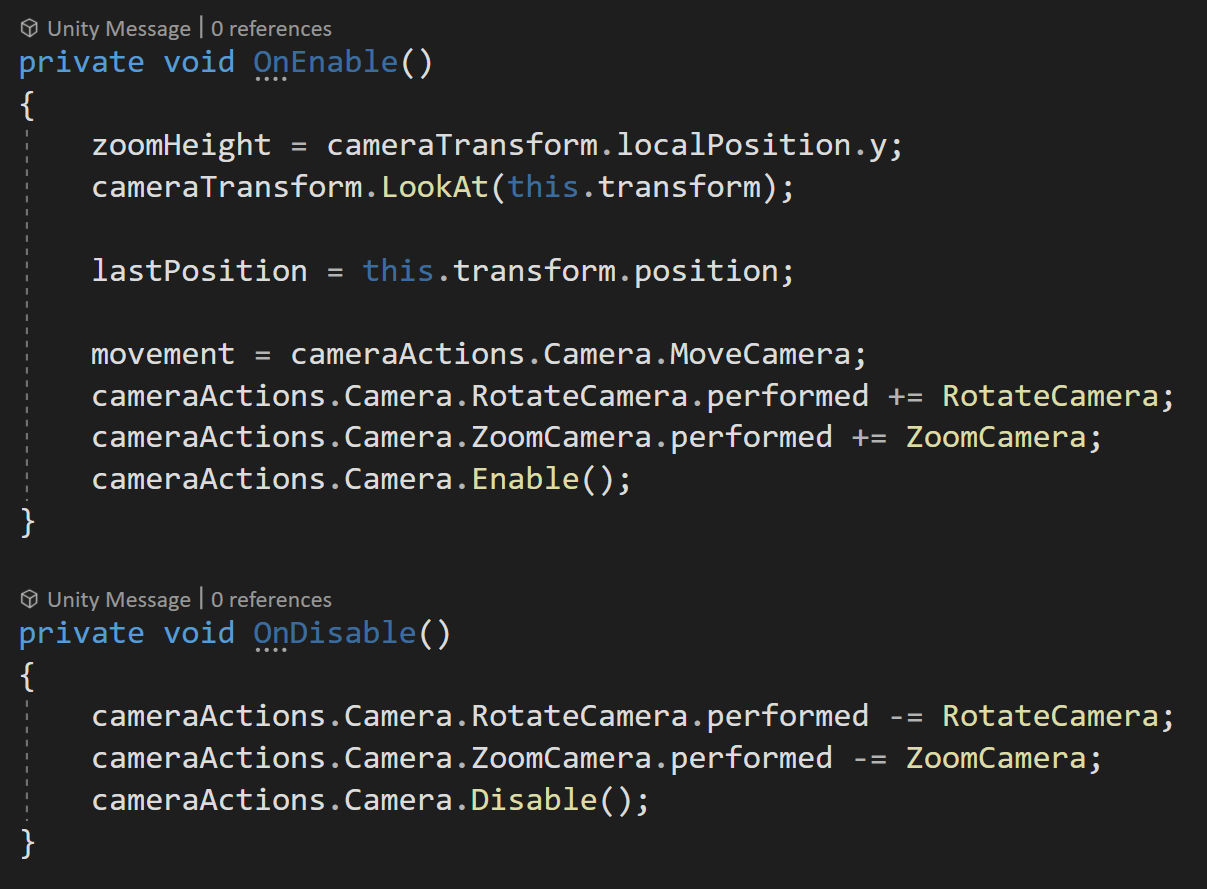

First, we need to set up our Awake, OnEnable, and OnDisable functions.

In the Awake function, we need to create an instance of our CameraControls input action asset. While we’re at it we can also grab a reference to the transform of our camera object.

In the OnEnable function, we first need to make sure our camera is looking in the correct direction - we can do this with the LookAt function directed towards the camera rig base object (the same object the code is attached to).

Then we can save the current position to our last position variable - this value will get used to help create smooth motion.

Next, we’ll cache a reference to our MoveCamera action - we’ll be directly polling the values for movement. We also need to call Enable on the Camera action map.

In OnDisable we’ll call Disable on the camera action map to avoid issues and errors in case this object or component gets turned off.

Helper functions to get camera relative directions

Next, we need to create two helper functions. These will return camera relative directions. In particular, we’ll be getting the forward and right directions. These are all we’ll need since the camera rig base will only move in the horizontal plane, we’ll also squash the y value of these vectors to zero for the same reason.

Kind of yucky. But gets the job done.

Admittedly I don’t love the next function. It feels a bit clumsy, but since I’m not using a rigidbody and I want the camera to smoothly speed up and slow down I need a way to calculate and track the velocity (in the horizontal plane). So thus the Update Velocity function.

Nothing too special in the function other than once again squashing the y dimension of the velocity to zero. After calculating the velocity we update the value of the last position for the next frame. This ensures we are calculating the velocity for the frame and not from the start.

The next function is the poorly named Get Keyboard Movement function. This function polls the Camera Movement action to then set the target position.

In order to translate the input into the motion we want we need to be a bit careful. We’ll take the x component of the input and multiply it by the Camera Right function and add that to the y component of the input multiplied by the Camera Forward function. This ensures that the movement is in the horizontal plane and relative to the camera.

We then normalize the resulting vector to keep a uniform length so that the speed will be constant even if multiple keys are pressed (up and right for example).

The last step is to check if the input value’s square magnitude is above a threshold, if it is we add our input value to our target position.

Note that we are NOT moving the object here since eventually there will be multiple ways to move the camera base, we are instead adding the input to a target position vector and our NEXT function will use this target position to actually move the camera base.

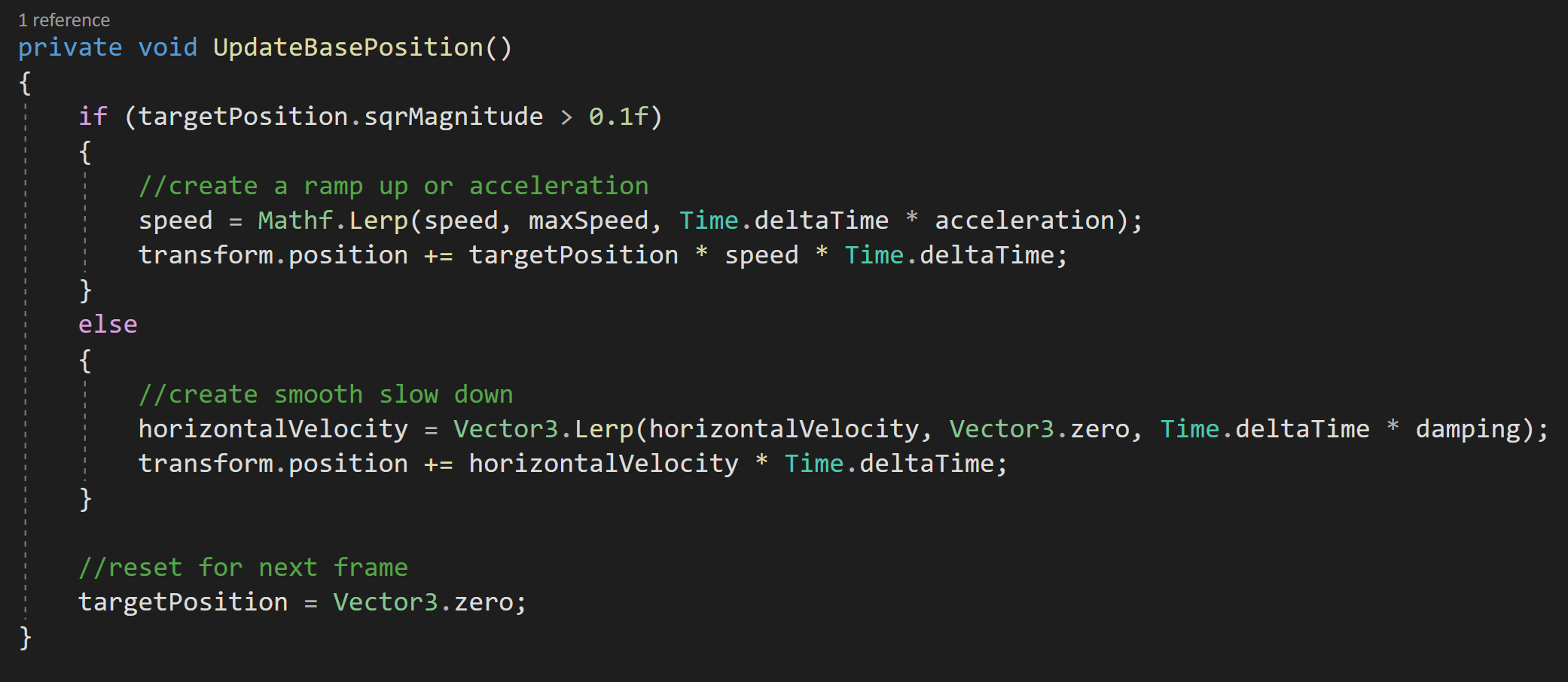

If we were okay with herky-jerky movement the next function would be much simpler. If we were using the physics engine (rigidbody) to move the camera it would also be simpler. But I want smooth motion AND I don’t want to tune a rigidbody. So to create smooth ramping up and down of speed we need to do some work. This work will all happen in the Update Base Position function.

First, we’ll check if the square magnitude of the target position is greater than a threshold value. If it is this means the player is trying to get the camera to move. If that’s the case we’ll lerp our current speed up to the max speed. Note that we’re also multiplying Time Delta Time by our acceleration. The acceleration allows us to tune how quickly our camera gets up to speed.

The use of the threshold value is for two reasons. One so we aren’t comparing a float to zero, i.e. asking if a float equals zero can be problematic. Two, if we were using a game controller joystick even if it’s at rest the input value may not be zero.

Testing the Code so far - Smooth Horizontal Motion

We then add to the transform’s position an amount equal to the target position multiplied by the current camera speed and time delta time.

While they might look different these two lines of code are closely related to the Kinematic equations you may have learned in high school physics.

If the player is not trying to get the camera to move we want the camera to smoothly come to a stop. To do this we want to lerp our horizontal velocity (calculated constantly by the previous function) down to zero. Note rather than using our acceleration to control the rate of the slow down, I’ve used a different variable (damping) to allow separate control.

With the horizontal velocity lerping it’s way towards zero, we then add to the transform’s position a value equal to the horizontal velocity multiplied by time delta time.

The final step is to set the target position to zero to reset for the next frame’s input.

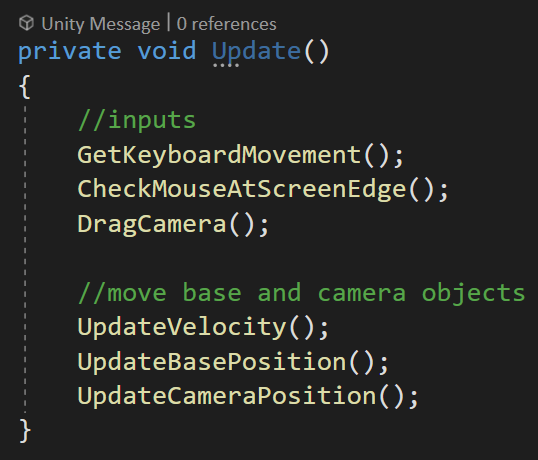

Our last step before we can test our code is to add our last three functions into the update function.

Camera Rotation

Okay. The hardest parts are over. Now we can add functionality reasonably quickly!

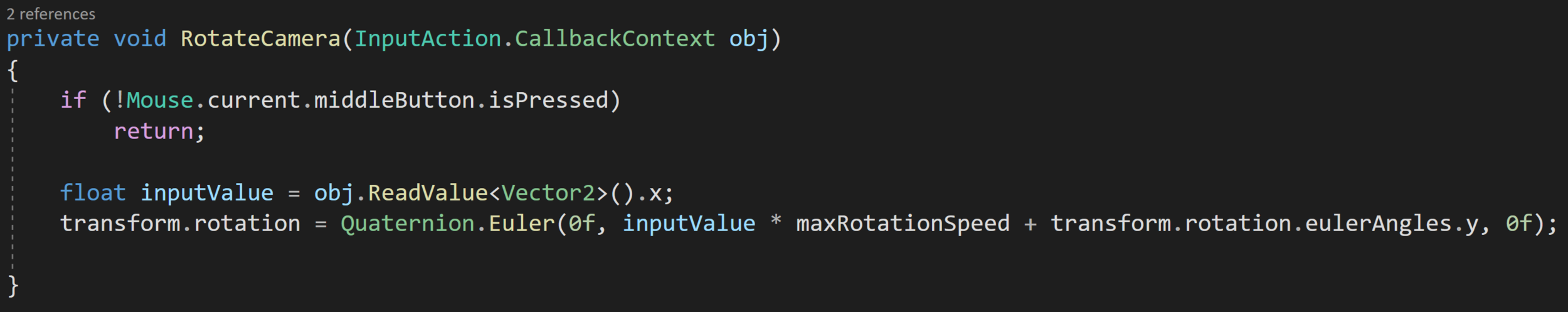

So let’s add the ability to rotate the camera. The rotation will be based on the delta or change in the mouse position and will only occur when the middle mouse button is pressed.

We’ll be using an event to trigger our rotation, so our first addition to our code is in our OnEnable and OnDisable functions. Here we’ll subscribe and unsubscribe the (soon to be created) Rotate Camera function to the performed event for the rotate camera action.

If you’re new to the input system, you’ll notice that the Rotate Camera function takes in a Callback Context object. This contains all the information about the action.

Rotating the camera should now be a thing!

Inside the function, we’ll first check if the middle mouse button is pressed. This ensures that the rotation doesn’t occur constantly but only when the button is pressed. For readability more than functionality, we’ll store the x value of the mouse delta and use it in the next line of code.

The last piece is to set the rotation of the transform (base object) and only on the y-axis. This is done using the x value of the mouse delta multiplied by the max rotation speed all added to the current y rotation.

And that’s it. With the event getting invoked there’s no need to add the function to our update function. Nice and easy.

Vertical Camera Motion

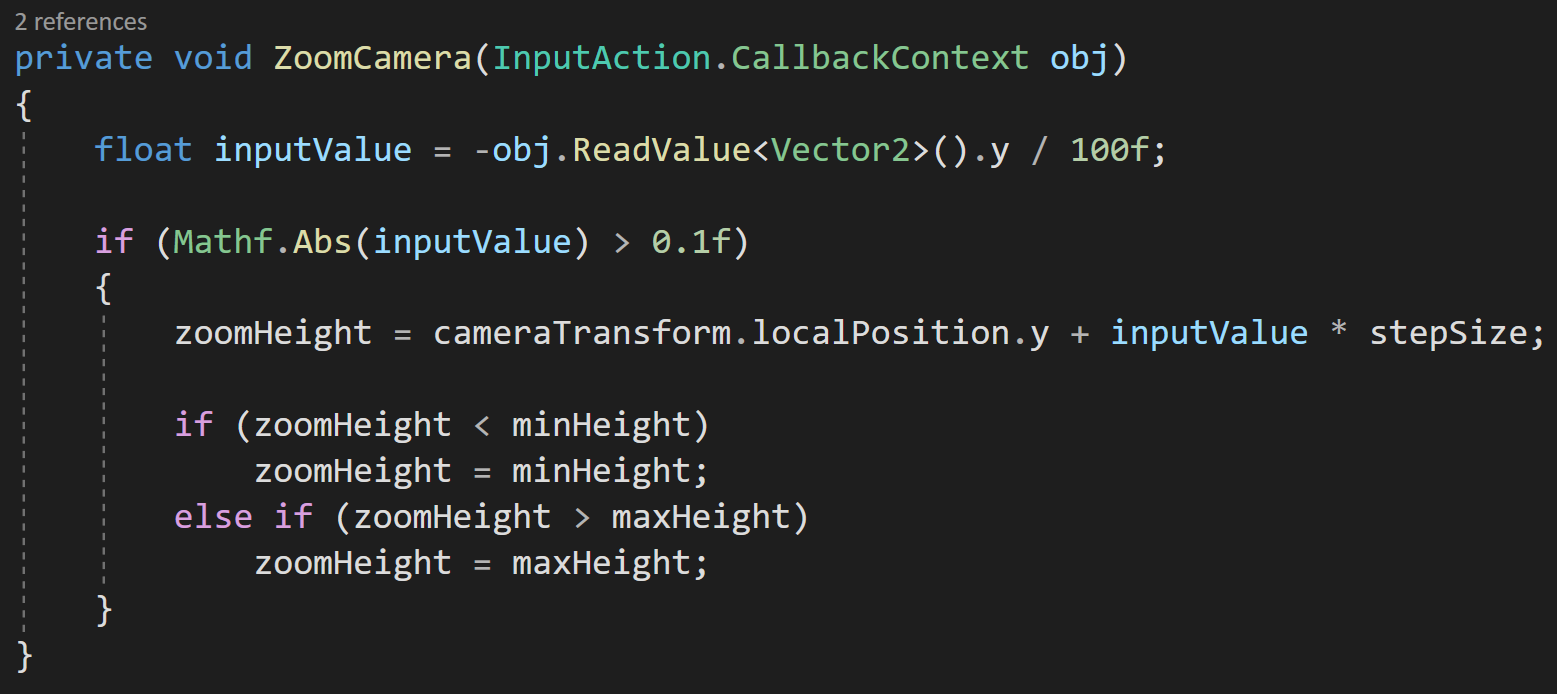

With horizontal and rotational motion working it would be nice to move the camera up and down to let the player see more or less of the world. For controlling the “zooming” we’ll be using the mouse scroll wheel.

This motion, I found to be one of the more complicated as there were several bits I wanted to include. I wanted there to be a min and max height for the camera - this keeps the player from zooming too far out or zooming down to nothingness - also while going up and down it feels a bit more natural if the camera gets closer or farther away from what it’s looking at.

This zoom motion is another good use of events so we need need to make a couple of additions to the OnEnable and OnDisable. Just like we did with the rotation we need to subscribe and unsubscribe to the performed event for the zoom camera action. We also need to set the value of zoom height equal to the local y position of the camera - this gives an initial value and prevents the camera from doing wacky things.

Then inside the Zoom Camera function, we’ll cache a reference to the y component of the scroll wheel input and divide by 100 - this scales the value to something more useful (in my opinion).

If the absolute value of the input value is greater than a threshold, meaning the player has moved the scroll wheel, we’ll set the zoom height to the local y position plus the input value multiplied by the step size. We then compare the predicted height to the min and max height. If the target height is outside of the allowed limits we set our height to the min or max height respectively.

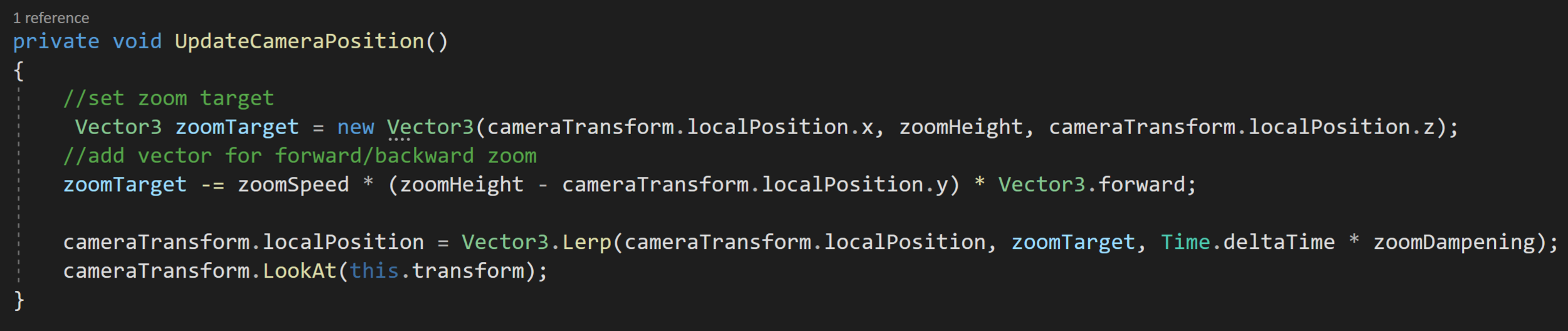

Once again this function isn’t doing the actual moving it’s just setting a target of sorts. The Update Camera Position function will do the actual moving of the camera.

The first step to move the camera is to use the value of the zoom height variable to create a Vector3 target for the camera to move towards.

Zooming in action

The next line is admittedly a bit confusing and is my attempt to create a zoom forward/backward motion while going up and down. Here we subtract a vector from our target location. The subtracted vector is a product of our zoom speed and the difference between the current height and the target height All of which is multiplied by the vector (0, 0, 1). This creates a vector proportional to how much we are moving vertically, but in the camera’s local forward/backward direction.

Our last steps are to lerp the camera’s position from its current position to the target location. We use our zoom damping variable to control the speed of the lerp.

Finally, we also have the camera look at the base to ensure we are still looking in the correct direction.

Before our zoom will work we need to add both functions to our update function.

If you are having weird zooming behavior it’s worth double-checking the initial position of the camera object. My values are shown at the top of the page. In my testing if the x position is not zero, some odd twisting motion occurs.

Mouse at Screen Edges

At this point, we have a pretty functional camera, but there’s still a bit more polish we can add. Many games allow the player to move the camera when the mouse is near the edges of the screen. Personally, I like this when playing games, but I do find it frustrating when working in Unity as the “screen edges” are defined by the game view…

To create this motion with the mouse all we need to do is check if the mouse is near the edge of the screen.

We do this by using Mouse.current.position.ReadValue(). This is very similar to the “old” input system where we could just call Input.MousePosition.

We also need a vector to track the motion that should occur - this allows the mouse to be in the corner and have the camera move in a diagonal direction.

Screen edge motion

Next, we simply check if the mouse x and y positions are less than or great than threshold values. The edge tolerance variable allows fine tuning of how close to the edge the cursor needs to be - in my case I’m using 0.05.

The mouse position is given to us in pixels not in screenspace coordinates so it’s important that we multiply by the screen width and height respectively. Notice that we are again making use of the GetCameraRight and GetCameraForward functions.

The last step inside the function is to add our move direction vector to the target position.

Since we are not using events this function also needs to get added to our update function.

Dragging the World

I stole and adapted the drag functionality from Game Dev Guide.

The last piece of polish I’m adding is the ability to click and drag the world. This makes for very fast motion and generally feels good. However, a note of caution when implementing this. Since we are using a mouse button to drag this can quickly interfere with other player actions such as placing units or buildings. For this reason, I’ve chosen to use the right mouse button for dragging. If you want to use the left mouse button you’ll need to check if you CAN or SHOULD drag - i.e. are you placing an object or doing something else with your left mouse button. In the past I have used a drag handler… so maybe that’s a better route, but it’s not the direction I choose to go at this point.

I should also admit that I stole and adapted much of the dragging code from a Game Dev Guide video which used the old input system.

Since dragging is an every frame type of thing, I’m once again going to directly poll to determine whether the right mouse button is down and to get the current position of the mouse…

This could probably be down with events, but that seems contrived and I’m not sure I really see the benefit. Maybe I’m wrong.

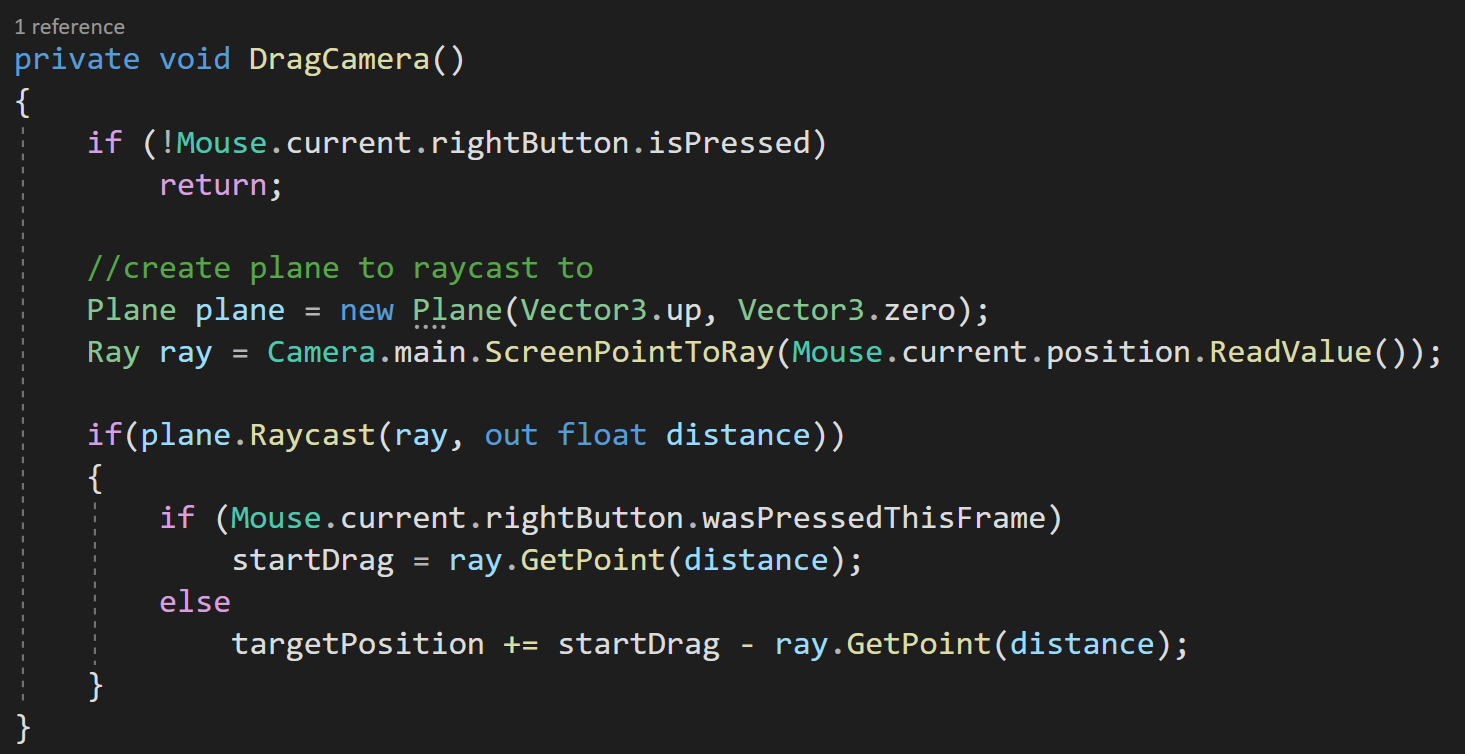

Inside the Drag Camera function, we can first check if the right button is pressed. If it’s not we don’t want to go any further.

If the button is pressed, we’re going to create a plane (I learned about this in the Game Dev Guide video) and a ray from the camera to the mouse cursor. The plane is aligned with the world XZ plane and is facing upward. When creating the plane the first parameter defines the normal and the second defines a point on the plane - which for the non-math nerds is all you need.

Next, we’ll raycast to the plane. So cool. I totally didn’t know this was a thing!

The out variable of distance tells us how far the ray went before it hit the plane, assuming it hit the plane. If it did hit the plane we’re going to do two different things - depending on whether we just started dragging or if we are continuing to drag.

Dragging the world

If the right mouse button was pressed this frame (learned about this thanks to a YouTube comment) we’ll cache the point on the plane that we hit. And we get that point, by using the Get Point function on our ray.

If the right mouse button wasn’t pressed this frame, meaning we are actively dragging, we can update the target position variable with the vector from where dragging started to where it currently is.

The final step is to add the drag function to our update function.

That’s It!

There you go. The basics of a strategy camera for Unity using the New Input System. Hopefully, this gives you a jumping off point to refine and maybe add features to your own camera controller.

Raycasting - It's mighty useful

Converting the examples to use the new input system. Please check the pinned comment on YouTube for some error correction.

What is Raycasting?

Raycasting is a lightweight and performant way to reach out into a scene and see what objects are in a given direction. You can think of it as something like a long stick used to poke and prod around a scene. When something is found, we can get all kinds of info about that object and have access

So… It’s pretty useful and a tool you should have in your game development toolbox.

Three Important Bits

The examples here are all going to be 3D, if you are working on a 2D project the ideas and concepts are nearly identical - with the biggest difference being that the code implementation is a tad different.

It’s also worth noting that the code for all the raycasting in the following examples, except for the jumping example, can be put on any object in the scene, whether that is the player or maybe some form of manager.

The final and really important tidbit is that raycasting is part of the physics engine. This means that for raycasting to hit or find an object, that object needs to have a collider or a trigger on it. I can’t tell you how many hours I’ve spent trying to debug raycasting only to find I forgot to put a collider on an object.

But First! The Basics.

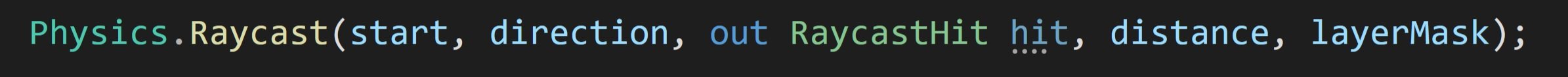

The basics Raycast function

We need to look at the Raycast function itself. The function has a ton of overloads which can be pretty confusing when you’re first getting started.

That said using the function basically breaks down into 5 pieces of information - the first two of which are required in all versions of the function. Those pieces of information are:

A start position.

The direction to send the ray.

A RaycastHit, which contains all the information about the object that was hit.

How far to send the ray.

Which layers can be hit by the raycast.

It’s a lot, but not too bad.

Defining a ray with start positon and the direction (both Vector3)

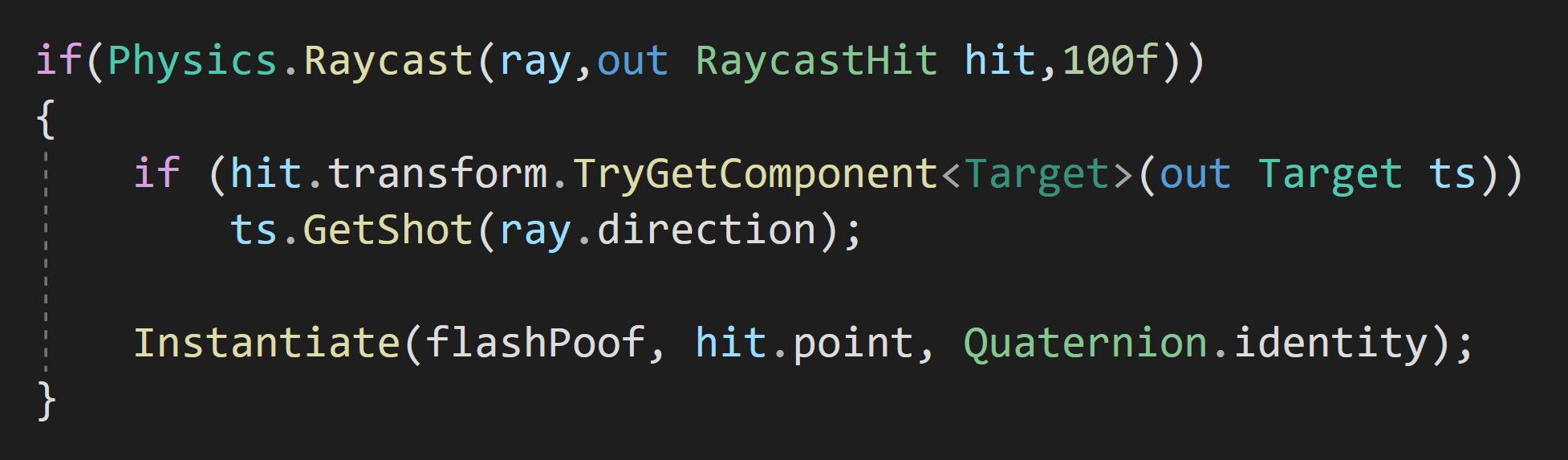

Raycast using a Ray

Unity does allow us to simplify the input para, just a bit, with the use of a ray. A ray essentially stores the start position and the direction in one container allowing us to reduce the number of input parameters for the raycast function by one.

Notice that we are defining the RaycastHit inline with the use of the keyword out. This effectively creates a local variable with fewer lines of code.

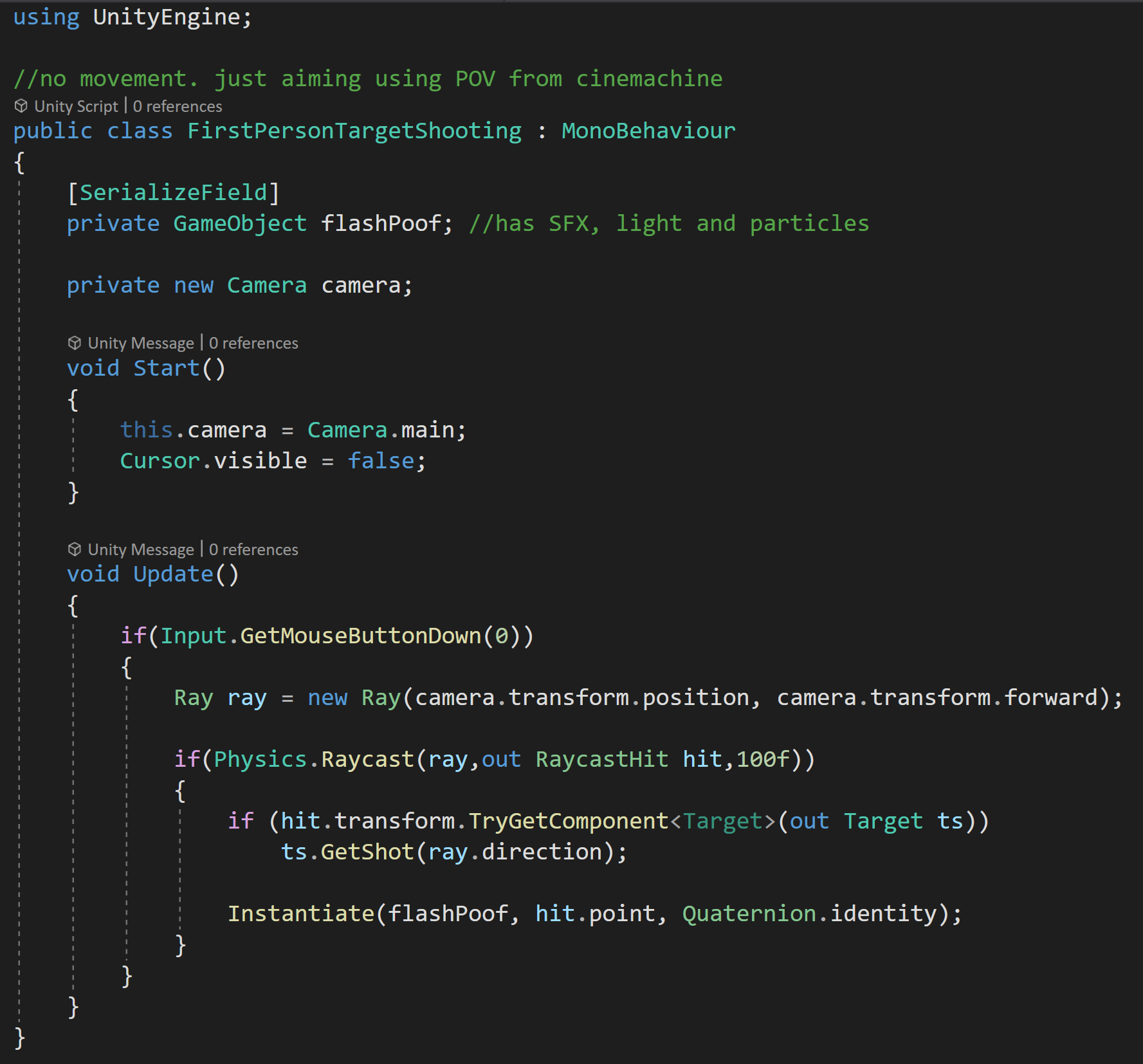

Ok Now Onto Shooting

Creating a ray from the camera through the center of the screen

To apply this to first-person shooting, we need a ray that starts at the camera and goes in the camera’s forward direction.

Then since the raycast function returns a boolean, true if it hits something, false if it didn’t, we can wrap the raycast in an if statement.

In this case, we could forgo the distance, but I’ll set it to something reasonable. I will, however, skip the layer mask as I want to be able to shoot at everything in the scene so the layer mask isn’t needed.

When I do hit something I want some player feedback so I’ll instantiate a prefab at the hit point. In my case, the prefab has a particle system, a light, and an audio source just to make shooting a bit more fun.

Okay, but what if we want to do something different when we hit a particular type of target?

There are several ways to do this, the way I chose was to add a script to the target (purple sphere) that has a public “GetShot” function. This function takes in the direction from the ray and then applies a force in that direction plus a little upward force to add some extra juice.

Complete first person shooting example

The unparenting at the end of the GetShot function is to avoid any scaling issues as the spheres are parented to the cubes below them.

Then back to the raycast, we can check if the object we hit has a “Target” component on it. If it does, we call the “GetShot” function and pass in the direction from the ray.

The function getting called could of course be on a player or NPC script and do damage or any other number of things needed for your game.

The RaycastHit gives us access to the object hit and thus all the components on that object so we can do just about anything we need.

But! We still need some way to trigger this raycast and we can do that by wrapping it all in another if statement that checks if the left mouse button was pressed. And all of that can go into our update function so we check every frame.

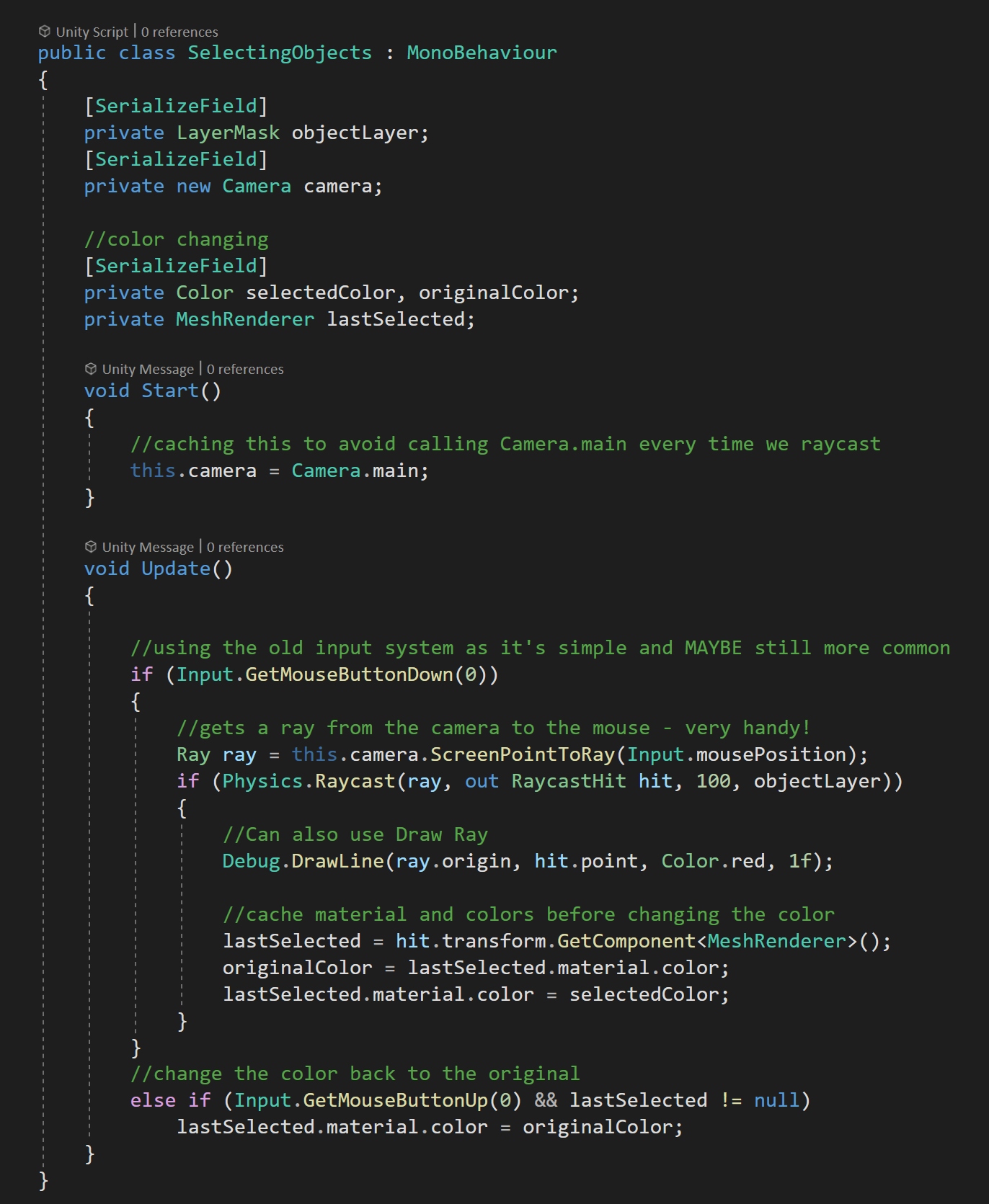

Selecting Objects

Another common task in games is to click on objects with a mouse and have the object react in some way. As a simple example, we can click on an object to change its color and then have it go back to its original color when we let go of the mouse button.

To do this, We’ll need two extra variables to hold references to a mesh renderer as well as the color of the material on that mesh renderer.

For this example, I am going to use a layer mask. To make use of the layer mask, I’ve created a new layer called “selectable” and changed the layer of all the cubes and spheres in the scene, and left the rest of the objects on the default layer. This will prevent us from clicking on the background and changing its color.

Complete code for Toggling objects color

Then in the script, I created a private serialized field of the type layer mask. Flipping back into Unity the value of the layer mask can be set to “selectable.”

Then if and else if statements check for the left mouse button being pressed and released, respectively.

If the button is pressed we’ll need to raycast and in this case, we need to create a ray from the camera to the mouse position.

Thankfully Unity has given us a nice built function that does this for us!

With our ray created we can add our raycast function, using the created ray, a RaycastHit, a reasonable distance, and our layer mask.

If we hit an object on our selectable layer, we can cache the mesh renderer and the color of the first material. The caching is so when we release the mouse button we can restore the color to the correct material on the correct mesh renderer.

Not too bad.

Notice that I’ve also added the function Debug.DrawLine. When getting started with raycasting it is SUPER easy to get rays going in the wrong direction or maybe not going far enough.

The DrawLine function does just as it says drawing a line from one point to another. There is also a duration parameter, which is how long the line is drawn in seconds which can be particularly helpful when raycasting is only done for one frame at time.

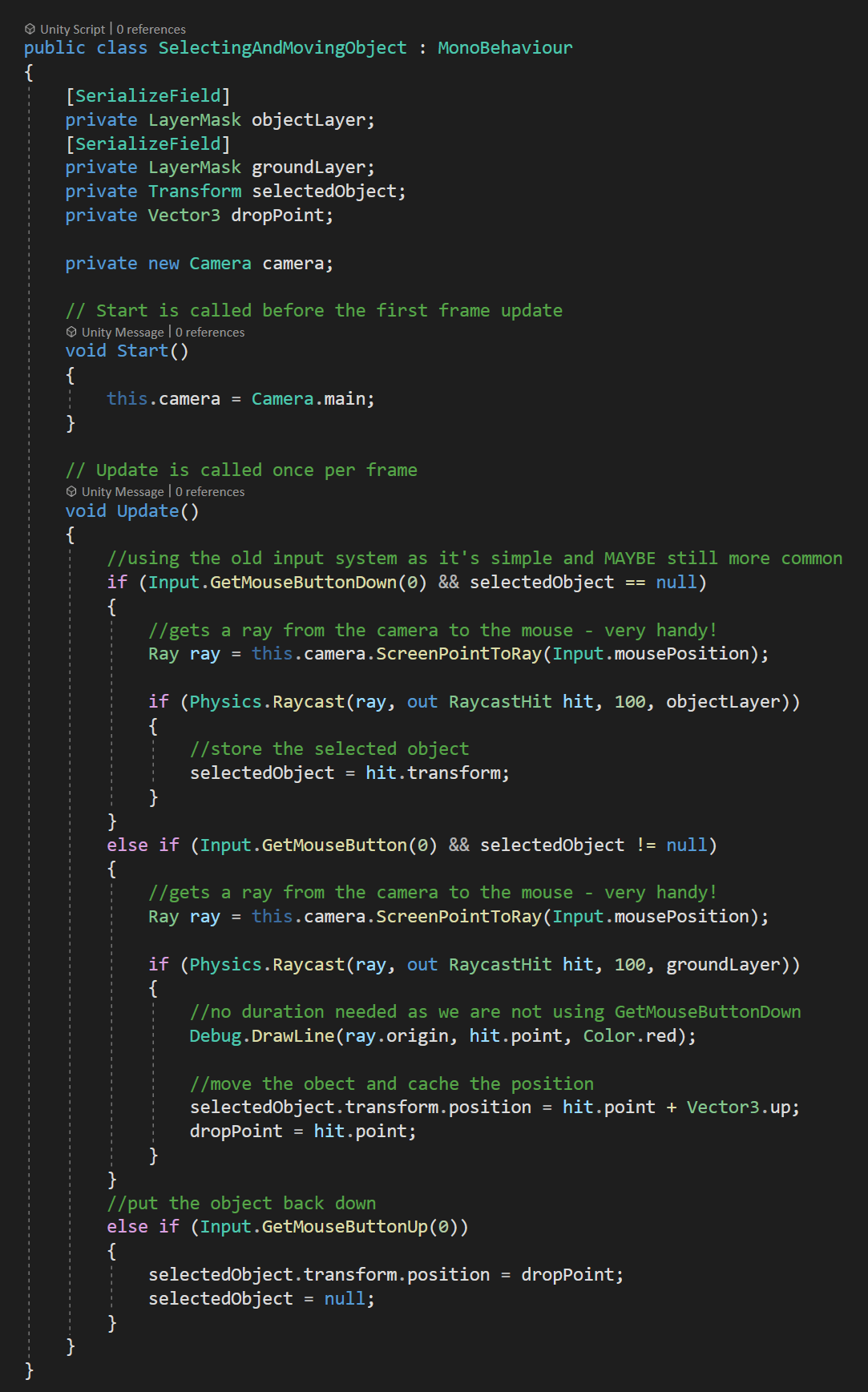

Moving Objects

Now at first glance moving objects seems very similar to selecting objects - raycast to the object and move the object to the hit point. I’ve done this a lot…

The problem is the object comes screaming towards the camera, because the hit point is closer to the camera than the objects center. Probably not what you or your players want to happen.

Don’t do this!!

One way around this is to use one raycast to select the object and a second raycast to move the object. Each raycast will use a different layer mask to avoid the flying cube problem.

I’ve added a “ground” layer to the project and assigned it to the plane in the scene. The “selectable” layer is assigned to all the cubes and spheres. The values for the layer masks can again be set in the inspector.

To make this all work, we’re also going to need variables to keep track of the selected object (Transform) and the last point hit by the raycast (Vector3).

To get our selected object, we’ll first check if the left mouse button has been clicked and if the selected object is currently null. If both are true, we’ll use a raycast just like the last example to store a reference to the transform of the object we clicked on.

Note the use of the “object” layer mask in the raycast function.

Our second raycast happens when the left mouse button is held down AND the selected object is NOT null. Just like the first raycast this one goes from the camera to the mouse, but it makes use of the second layer mask, which allows the ray to go through the selected object and hit the ground.

We now move the selected object to the point hit by the ray cast, plus for just for fun, we move it up a bit as well. This lets us drag the object around.

If we left it like this and let go of the mouse button the object would stay levitated above the ground. So instead, when the mouse button comes up we can set the position to the last point hit by the raycast as well as setting the selectedObject variable to null - allowing us to select a new object.

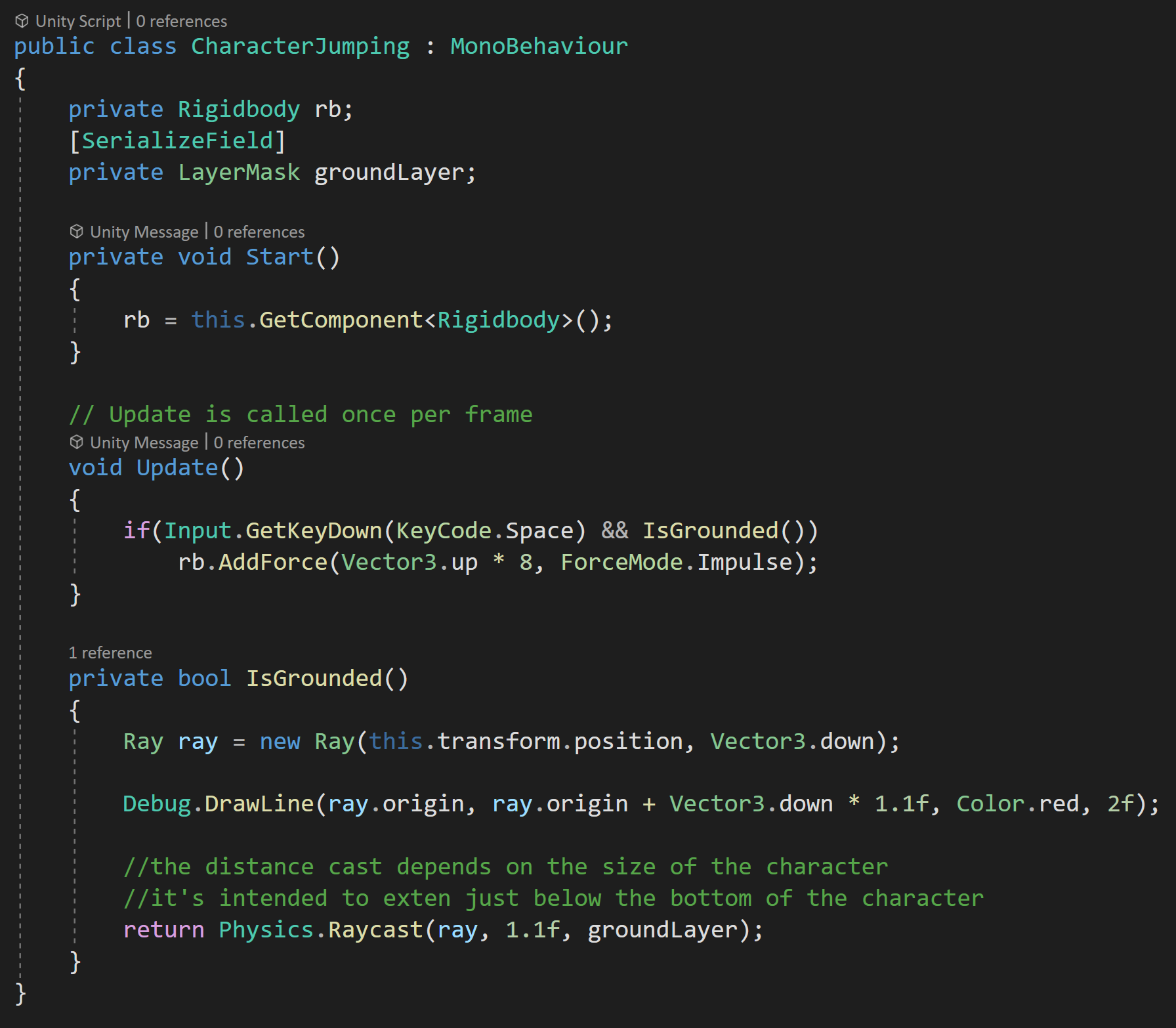

Jumping

The last example I want to go over in any depth is jumping, which can be easily extended to other platforming needs like detecting a wall or a slope or the edge of a platform - I’d strongly suggest checking out Sebastian Lague’s series on creating a 2D platformer if you want to see raycasting put to serious use not mention a pretty good character controller for a 2D game!

For this example, I’ve created a variable to store the rigidbody and I’ve cached a reference to that rigidbody in the start function.

For basic jumping, generally, the player needs to be on the ground in order to jump. You could use a trigger combined with OnTriggerEnter and OnTriggerExit to track if the player is touching the ground, but that’s clumsy and has limitations.

Instead, we can do a simple short raycast directly down from the player object to check and see if we’re near the ground. Once again this makes use of layer mask and in this case only casts to the ground layer.

Full code for jumping

I’ve wrapped the raycast into a separate function that returns the boolean from the raycast. The ray itself goes from the center of the player character in the down direction. The raycast distance is set to 1.1 since the player object (a capsule) is 2 meters high and I want the raycast to extend just beyond the object. If the raycast extends too far, the ground can be detected when the player is off the ground and the player will be able to jump while in the air.

I’ve also added in a Debug.DrawLine function to be able to double-check that the ray is in the correct place and reaching outside the player object.

Then in the update function, we check if the spacebar is pressed along with whether the player is on the ground. If both are true we apply force to the rigidbody and it the the player jumps.

RaycastHit

The real star of the raycasting show is the RaycastHit variable.

It’s how we get a handle on the object the raycast found and there’s a decent amount of information that it can give us. In all the examples above we made use of “point” to get the exact coordinates of the hit. For me this is what I’m using 9 times out of 10 or even more when I raycast.

We can also get access to the normal of the surface we hit, which among other things could be useful if you want something to ricochet off a surface or if you want to have a placed object sit flat on a surface.

The RaycastHit can also return the distance from the ray’s origin to the hit point as well as the rigidbody that was hit (if there was one).

If you want to get really fancy you can also access bits about the geometry and the textures at the hit point.

Other Things Worth Knowing

So there’s 4 examples of common uses of raycasting, but there are a few other bits of info that could be good to know too.

There is an additional input for raycasting which is Physics.queriesHitTriggers. Be default this parameter is true and if its true raycasts will hit triggers. If it’s false the raycast will skip triggers. This could be helpful for raycasting to NPCs that have a collider on their body, but also have a larger trigger surrounding them to detect nearby objects.

Next useful bit. If you don’t set a distance for a raycast, Unity will default to an infinite distance - whatever infinity means to a computer… There could be several reasons not to allow the ray to go to infinity - the jump example is one of those.

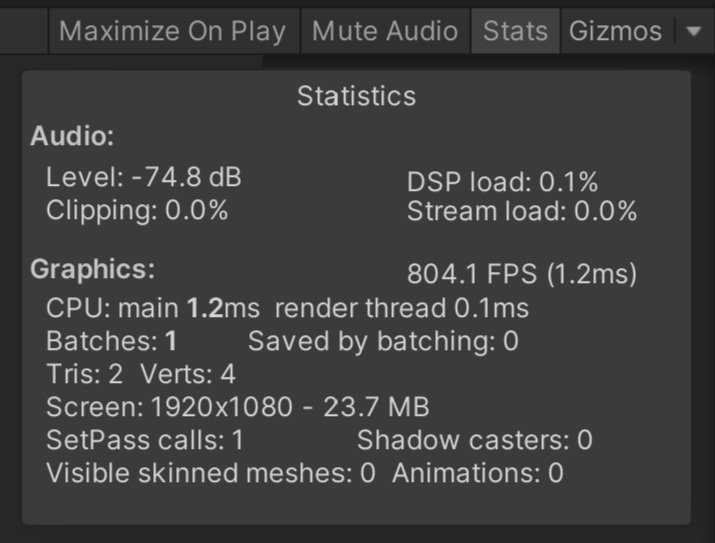

A very non precise or accurate way of measures performance

Raycasting can get a bad rap for performance. The truth is it’s pretty lightweight.

I created a simple example that raycasts between 1 and 1000 times per frame. In an empty scene on my computer with 1 raycast I saw over 5000 fps. With a 1000 raycasts per FRAME I saw 800 fps. More importantly, but no more precisely measured, the main thread only took a 1.0 ms hit when going from 1 raycast to 1000 raycasts which isn’t insignificant, but it’s also not game-breaking. So if you are doing 10 or 20 raycasts or even 100 raycasts per frame it’s probably not something you need to worry about.

1 Raycast per Frame

1000 Raycasts per Frame

Also worth knowing about, is the RaycastAll function. Which will return all objects the ray intersects, not just the first object. Definitely useful in the right situation.

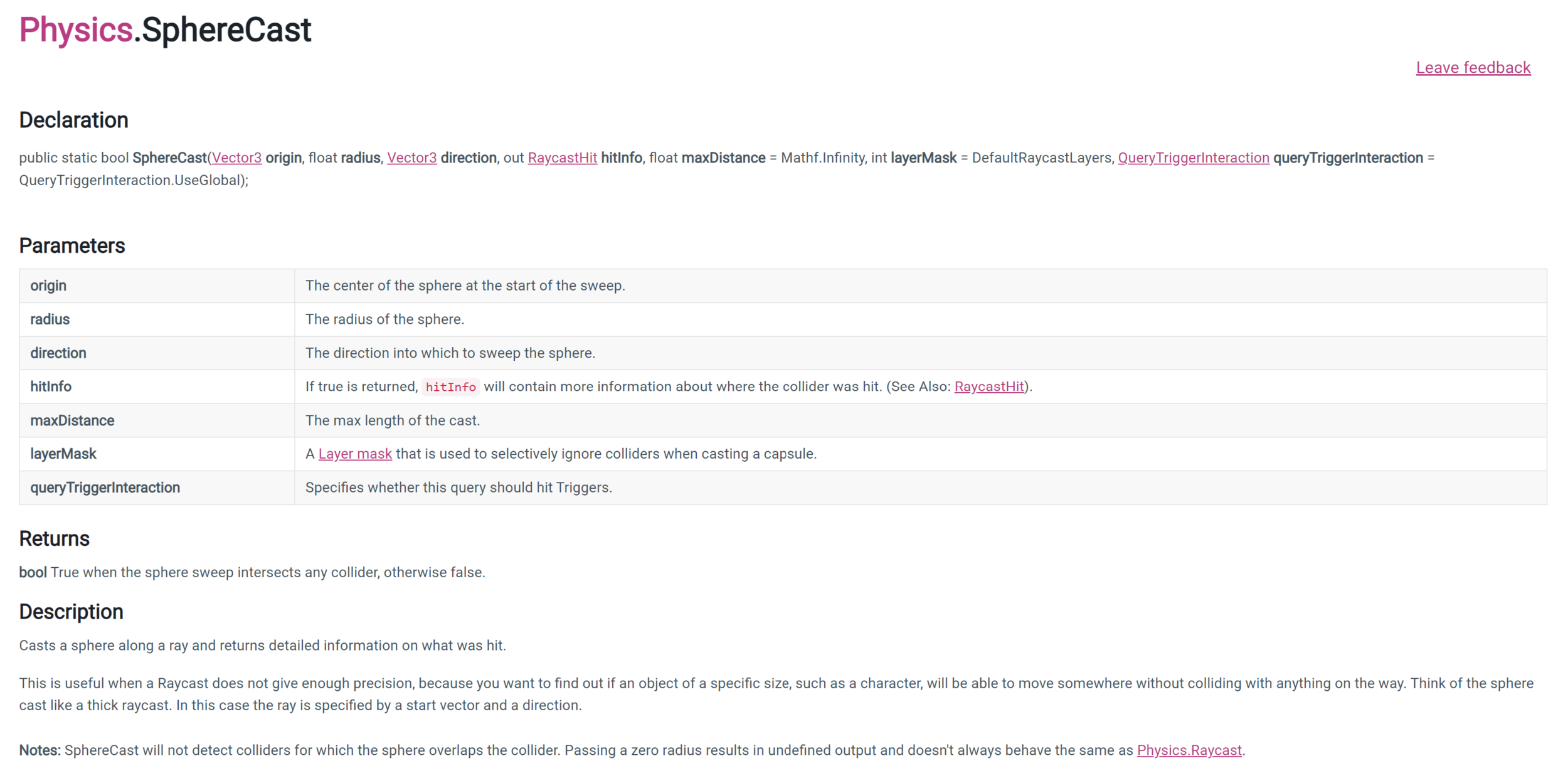

Lastly, there are other types of “casting” not just raycasting. There is line casting, box casting, and sphere casting. All of which use their respective geometric shape and check for colliders and triggers in their path. Again useful in the right situation - but beyond the scope of this tutorial.

Cinemachine. If you’re not. You should.

So full disclosure! This isn’t intended to be the easy one-off tutorial showing you how to make a particular thing. I want to get there, but this isn’t it. Instead, this is an intro. An overview.

If you’re looking for “How do I make an MMO RPG RTS 2nd Person Camera” this isn’t the tutorial for you. But! I learned a ton while researching Cinemachine (i.e. reading the documentation and experimenting) and I figured if I learned a ton then it might be worth sharing. Maybe I’m right. Maybe I’m not.

Cinemachine. What is it? What does it do?

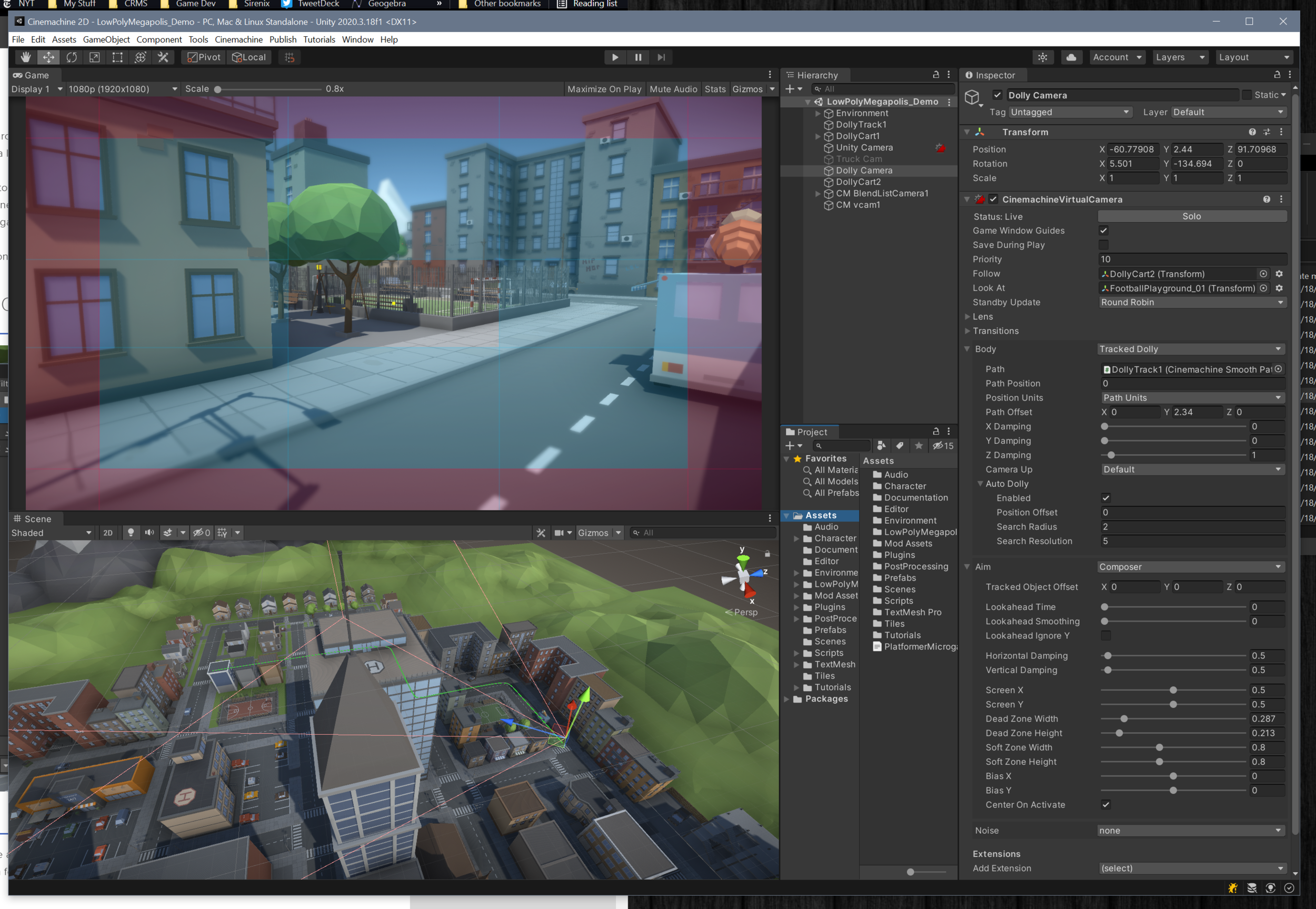

Cinemachine setup in the a Unity scene

Cinemachine is a Unity asset that quickly and easily creates high-functioning camera controllers without the need (but with the option) to write custom code. In just a matter of minutes, you can add Cinemachine to your project, drop in the needed prefabs and components and you’ll have a functioning 2D or 3D camera!

It really is that simple.

But!

If you’re like me you may have just fumbled your way through using Cinemachine and never really dug into what it can do, how it works, or the real capabilities of the asset. This leaves a lot of potential functionality undiscovered and unused.

Like I said above, this tutorial is going to be a bit different, many other tutorials cover the flashy bits or just a particular camera type, this post will attempt to be a brief overview of all the features that Cinemachine has to offer. Future posts will take a look at more specific use cases such as cameras for a 2D platformer, 3rd person games, or functionality useful for cutscenes and trailers.

If there’s a particular camera type, game type, or functionality you’d like to see leave a comment down below.

How do you get Cinemachine?

Cinemachine in the PAckage Manager

Cinemachine used to be a paid asset on the asset store and as I remember it, it was one of the first assets that Unity purchased and made free for all of its users! Nowadays it takes just a few clicks and a bit of patience with the Unity package manager to add Cinemachine to your project. Piece of cake.

The Setup

Once you’ve added Cinemachine to your project the next step is to add a Cinemachine Brain to your Unity Camera. The brain must be on the same object as the Unity camera component since it functions as the communication link between the Unity camera and any of the Cinemachine Virtual Cameras that are in the scene. The brain also controls the cut or blend from one virtual camera to another - pretty handy when creating a cut scene or recording footage for a trailer. Additionally, the brain is also able to fire events when the shot changes like when a virtual camera goes live - once again particularly useful for trailers and cutscenes.

Cinemachine Brain

Cinemachine does not add more camera components to your scene, but instead makes use of so-called “virtual cameras.” These virtual cameras control the position and rotation of the Unity camera - you can think of a virtual camera as a camera controller, not an actual camera component. There are several types of Cinemachine Virtual Cameras each with a different purpose and different use. It is also possible to program your own Virtual Camera or extend one of the existing virtual cameras. For most of us, the stock cameras should be just fine and do everything we need with just a bit of tweaking and fine-tuning.

Cinemachine offers several prefabs or presets for virtual camera objects - you can find them all in the Cinemachine menu. Or if you prefer you can always build your own by adding components to gameObjects - the same way everything else in Unity gets put together.

As I did my research, I was surprised at the breadth of functionality, so at the risk of being boring, let’s quickly walk through the functionality of each Cinemachine prefab.

Virtual Cameras

Bare Bones Basic Virtual Camera inspector

The Virtual Camera is the barebones base virtual camera component slapped onto a gameObject with no significant default values. Other virtual cameras use this component (or extend it) but with different presets or default values to create specific functionality.

The Freelook Camera provides an out-of-the-box and ready-to-go 3rd person camera. Its most notable feature is the rigs that allow you to control and adjust where the camera is allowed to go relative to the player character or more specifically the Look At target. If you’re itching to build a 3rd person controller - check out my earlier video using the new input system and Cinemachine.

The 2D Camera is pretty much what it sounds like and is the virtual camera to use for typical 2D games. Settings like softzone, deadzone and look ahead time are really easy to dial in and get a good feeling camera super quick. This is a camera I intend to look at more in-depth in a future tutorial.

The Dolly Camera will follow along on a track that can be easily created in the scene view. You can also add a Cart component to an object and just like the dolly camera, the cart will follow a track. These can be useful to create moving objects (cart) or move a (dolly) camera through a scene on a set path. Great for cutscenes or footage for a trailer.

“Composite” Cameras

The word “composite” is my word. The prefabs below use a controlling script for multiple children cameras and don’t function the same as a single virtual camera. Instead, they’re a composite of different objects and multiple different virtual cameras.

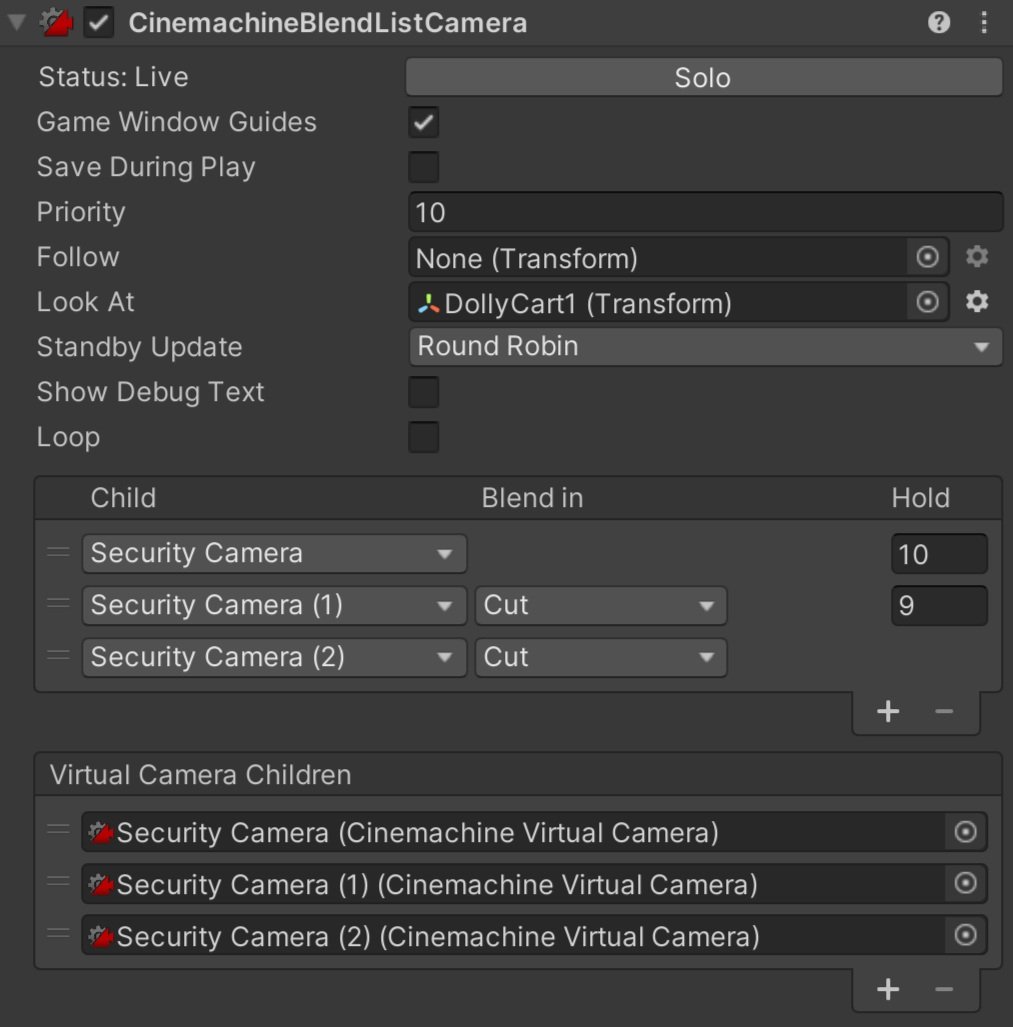

Some of these composite cameras are easier to set up than others. I found the Blend List camera 100% easy and intuitive. Whereas the Clear Shot camera? I got it working but only by tinkering with settings that I didn’t think I’d need to adjust. The 10 minutes spent tinkering is still orders of magnitude quicker than trying to create my own system!!

The Blend List Camera allows you to create a list of cameras and blend from one camera to another after a set amount of time. This would be super powerful for recording footage for a trailer.

Blend List Camera

The State-Driven Camera is designed to blend between cameras based on the state of an animator. So when an animator transitions, from say running to idle, you might switch to a different virtual camera that has different settings for damping or a different look-ahead time. Talk about adding some polish!

The ClearShot Camera can be used to set up multiple cameras and then have Cinemachine choose the camera that has the best shot of the target. This could be useful in complex scenes with moving objects to ensure that the target is always seen or at least is seen the best that it can be seen. This has similar functionality to the Blend List Camera, but doesn’t need to have timings hard coded.

The Target Group Camera component can act as a “Look At” target for a virtual camera. This component ensures that a list of transforms (assigned on the Target Group Camera component) stays in view by moving the camera accordingly.

Out of the Box settings with Group Target - Doing its best to keep the 3 cars in the viewport

The Mixing Camera is used to set the position and rotation of a Unity camera based on the weights of its children's cameras. This can be used in combination with animating the weights of the virtual cameras to move the Unity camera through a scene. I think of this as creating a bunch of waypoints and then lerping from one waypoint to the next. Other properties besides position and rotation are mixed.

Ok. That’s a lot. Take a break. Get a drink of water, because that’s the prefabs, and there’s still a lot more to come!

Shared Camera Settings

There are a few settings that are shared between all or most of the virtual cameras and the cameras that don’t share very many settings fall into the “Composite Camera” category and have children cameras that DO share the settings. So let’s dive into those settings to get a better idea of what they all do and most importantly what we can then do with the Cinemachine.

All the common and shared virtual camera settings

The Status line, I find a bit odd, it shows whether the camera is Live, in Standby, or Disabled which is straightforward enough, but the “Solo” button next to the status feels like an odd fit. Clicking this button will immediately give visual feedback from that particular camera, i.e. treating this camera as if it is the only or solo camera in the scene? If you are working on a complex cutscene with multiple cameras I can see this feature being very useful.

The Follow Target is the transform for the object that the virtual camera will move with or will attempt to follow based on the algorithm chosen. This is not required for the “composite” cameras but all the virtual cameras will need a follow target.

The Look At Target is the transform for the object that the virtual camera will aim at or will try to keep in view. Often this is the same as the Follow Target, but not always.

The Standby Update determines the interval that the virtual camera will be updated. Always, will update the virtual camera every frame whether the camera is live or not. Never, will only update the camera when it is live. Round Robin, is the default setting and will update the camera occasionally depending on how many other virtual cameras are in the scene.

The Lens gives access to the lens settings on the Unity camera. This can allow you to change those settings per virtual camera. This includes a Dutch setting that rotates the camera on the z-axis.

The Transitions settings allow customization of the blending or transition from one virtual came to or from this camera.

Body

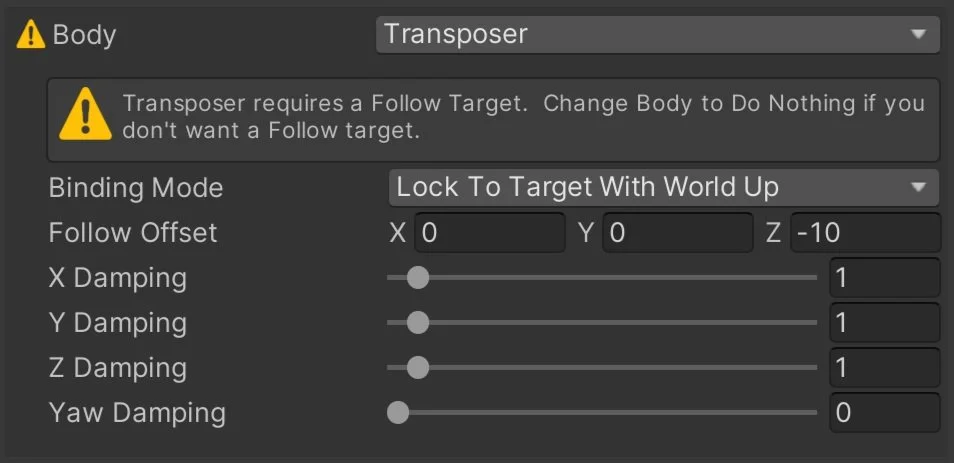

The Body controls how the camera moves and is where we really get to start customizing the behavior of the camera. The first slot on the body sets the algorithm that will be used to move the camera. The algorithm chosen will dictate what further settings are available.

It’s worth noting that each algorithm selected in the Body works alongside the algorithm selected in the Aim (coming up next). Since these two algorithms work together no one algorithm will define or create complete behavior.

The transposer moves the camera in a fixed relationship to the follow target as well as applies an offset and damping.

The framing transposer moves the camera in a fixed screen-space relationship to the Follow Target. This is commonly used for 2D cameras. This algorithm has a wide range of settings to allow you to fine-tune the feel of the camera.

The orbital transposer moves the camera in a variable relationship to the Follow Target, but attempts to align its view with the direction of motion of the Follow Target. This is used in the free-look camera and among other things can be used for a 3rd person camera. I could also imagine this being used for a RTS style camera where the Follow Target is an empty object moving around the scene.

The tracked dolly is used to follow a predefined path - the dolly track. Pretty straightforward.

Dolly track (Green) Path through a Low Poly Urban Scene

Hard lock to target simply sticks the camera at the same position as the Follow Target. The same effect as setting a camera as a child object - but with the added benefit of it being a virtual camera not an actual Unity camera component that has to be managed. Maybe you’re creating a game with vehicles and you want the player to be able to choose their perspective with one or more of those fixed to the position in the vehicle?

The “do nothing” transposer doesn’t move the camera with the Follow Target. This could be useful for a camera that shouldn’t move or should be fixed to another object but might still need to aim or look at a target. Maybe for something like a security-style camera that is fixed on the side of a building but might still rotate to follow the character.

Aim

The Aim controls where the camera is pointed and is determined by which algorithm is used.

The composer works to keep the Look At target in the camera frame. There is a wide range of settings to fine-tune the behavior. These include look-ahead time, damping, dead zone and soft zone settings.

The group composer works just like the composer unless the Look At target is a Cinemachine Target Group. In that case, the field of view and distance will adjust to keep all the targets in view.

The POV rotates the camera based on user input. This allows mouse control in an FPS style.

The “same as follow target” does exactly as a says - which is to set the rotation of the virtual camera to the rotation of the Follow target.

“Hard look at” keeps the Look At target in the center of the camera frame.

Do Nothing. Yep. This one does nothing. While this sounds like an odd design choice, this is used with the 2D camera preset as no rotation or aiming is needed.

Noise

The noise settings allow the virtual camera to simulate camera shake. There are built-in noise profiles, but if that doesn’t do the trick you can also create your own.

Extensions

Cinemachine provides several out-of-the-box extensions that can add additional functionality to your virtual cameras. All the Cinemachine extensions extend the class CinemachineExtension, leaving the door open for developers to create their own extensions if needed. In addition, all existing extensions can also be modified.

Cinemachine Camera Offset applies an offset to the camera. The offset can be applied after the body, aim, noise or after the final processing.

Cinemachine Recomposer adds a final adjustment to the composition of the camera shot. This is intended to be used with Timeline to make manual adjustments.

Cinemachine 3rd Person Aim cancels out any rotation noise and forces a hard look at the target point. This is a bit more sophisticated than a simple “hard look at” as target objects can be filtered by layer and tags can be ignored. Also if an aiming reticule is used the extension will raycast to a target and move the reticule over the object to indicate that the object is targeted or would be hit if a shot was to be fired.

Cinemachine Collider adjusts the final position of the camera to attempt to preserve the line of sight to the Look At target. This is done by moving the camera away from gameObjects that obstruct the view. The obstacles are defined by layers and tags. You can also choose a strategy for moving the camera when an obstacle is encountered.

Cinemachine Confiner prevents the camera from moving outside of a collider. This works in both 2D and 3D projects. It’s a great way to prevent the player from seeing the edge of the world or seeing something they shouldn’t see.

Polygon collider setting limits for where the camera can move

Cinemachine Follow Zoom adjusts the field of view (FOV) of the camera to keep the target the same size on the screen no matter the camera or target position.

Cinemachince Storyboard allows artists and designers to add an image over the top of the camera view. This can be useful for composing scenes and helping to visualize what a scene should look like.

Cinemachine Impulse Listener works together with an Impulse Source to shake the camera. This can be thought of as a real-world camera that is not 100% solid and has some shake. A source could be set on a character’s feet and emit an impulse when the feet hit the ground. The camera could then react to that impulse.

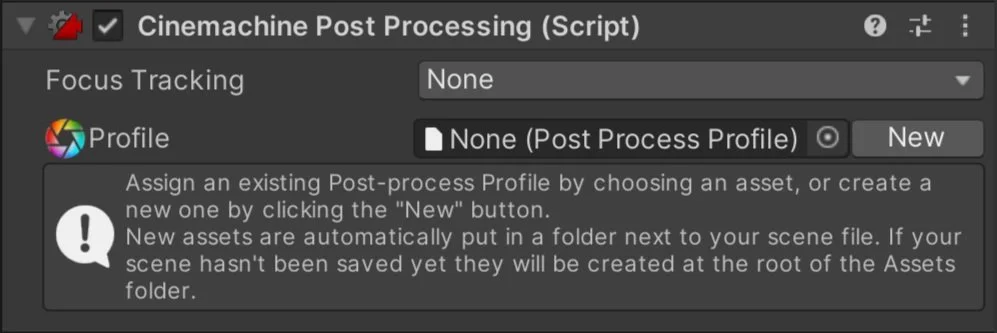

Cinemachine Post Processing allows a postprocessing (V2) profile to be attached to a virtual camera. Which lets each virtual camera have its own style and character.

There are probably even more… but these were the ones I found.

Conclusion?

Cinemachine is nothing short of amazing and a fantastic tool to speed up the development of your game. If you're not using it, you should be. Even if it doesn’t provide the perfect solution that ships with your project it provides a great starting point for quick prototyping.

If there’s a Cinemachine feature you’d like to see in more detail. Leave a comment down below.

A track and Dolly setup in the scene - I just think it looks neat.

Older Posts

-

January 2026

- Jan 27, 2026 Save and Load Framework Jan 27, 2026

-

April 2024

- Apr 10, 2024 Ready for Steam Next Fest? - Polishing a Steam Page Apr 10, 2024

- Apr 1, 2024 Splitting Vertices - Hard Edges for Low Poly Procedural Generation Apr 1, 2024

-

November 2023

- Nov 18, 2023 Minute 5 to Minute 10 - Completing the Game Loop Nov 18, 2023

-

September 2023

- Sep 13, 2023 Visual Debugging with Gizmos Sep 13, 2023

-

July 2023

- Jul 4, 2023 Easy Mode - Unity's New Input System Jul 4, 2023

-

May 2023

- May 19, 2023 Level Builder - From Pixels to Playable Level May 19, 2023

-

April 2023

- Apr 11, 2023 Input Action in the Inspector - New Input System Apr 11, 2023

-

February 2023

- Feb 26, 2023 Tutorial Hell - Why You're There. How to Get Out. Feb 26, 2023

-

December 2022

- Dec 31, 2022 Upgrade System (Stats Part 2) Dec 31, 2022

-

November 2022

- Nov 10, 2022 Stats in Unity - The Way I Do it Nov 10, 2022

- Nov 5, 2022 State of UI in Unity - UI Toolkit Nov 5, 2022

-

August 2022

- Aug 17, 2022 Knowing When A Coroutine Finishes Aug 17, 2022

-

April 2022

- Apr 23, 2022 Unity Input Event Handlers - Or Adding Juice the Easy Way Apr 23, 2022

-

March 2022

- Mar 15, 2022 *Quitting a Job I Love Mar 15, 2022

-

February 2022

- Feb 8, 2022 Split Screen: New Input System & Cinemachine Feb 8, 2022

-

January 2022

- Jan 24, 2022 (Better) Object Pooling Jan 24, 2022

- Jan 19, 2022 Designing a New Game - My Process Jan 19, 2022

- Jan 16, 2022 Strategy Game Camera: Unity's New Input System Jan 16, 2022

-

December 2021

- Dec 16, 2021 Raycasting - It's mighty useful Dec 16, 2021

-

November 2021

- Nov 22, 2021 Cinemachine. If you’re not. You should. Nov 22, 2021

-

August 2021

- Aug 3, 2021 C# Extension Methods Aug 3, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 27, 2021 Changing Action Maps with Unity's "New" Input System Jun 27, 2021

-

May 2021

- May 28, 2021 Unity's New Input System May 28, 2021

- May 8, 2021 Bolt vs. C# - Thoughts with a dash of rant May 8, 2021

-

March 2021

- Mar 10, 2021 Coroutines - Unity & C# Mar 10, 2021

-

January 2021

- Jan 14, 2021 Where's My Lunch? - January Devlog Update Jan 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 27, 2020 C# Generics and Unity Dec 27, 2020

- Dec 7, 2020 Steam Workshop with Unity and Facepunch Steamworks Dec 7, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 27, 2020 Simple Level Save and Load System (Unity Editor) Nov 27, 2020

- Nov 9, 2020 Command Pattern - Encapsulation, Undo and Redo Nov 9, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 28, 2020 GJTS - Adding Steamworks API and Uploading Oct 28, 2020

- Oct 9, 2020 Game Jam... Now What? Oct 9, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 16, 2020 Strategy Pattern - Composition over Inheritance Aug 16, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 24, 2020 Observer Pattern - C# Events Jul 24, 2020

- Jul 15, 2020 Object Pooling Jul 15, 2020

- Jul 3, 2020 Cheat Codes with Unity and C# Jul 3, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 16, 2020 The State Pattern Jun 16, 2020

-

August 2019

- Aug 12, 2019 Easy UI Styles for Unity Aug 12, 2019

-

July 2019

- Jul 3, 2019 9th Grade Math to the Rescue Jul 3, 2019

-

June 2019

- Jun 12, 2019 Introducing My Next Game (Video DevLog) Jun 12, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 29, 2019 Programming Challenges May 29, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 2, 2019 Something New - Asking "What Can I Learn?" Mar 2, 2019

-

November 2018

- Nov 30, 2018 A Growing Channel and a New Tutorial Series Nov 30, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 11, 2018 Procedural Spaceship Generator Oct 11, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 11, 2018 Implementing SFX in Unity Jul 11, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 31, 2018 Prototyping Something New May 31, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 17, 2018 When to Shelve a Game Project? Apr 17, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 9, 2018 State of the Game - Episode 3 Feb 9, 2018

-

December 2017

- Dec 16, 2017 State of the Game - Episode 2 Dec 16, 2017

-

November 2017

- Nov 7, 2017 The Bump From A "Viral" Post Nov 7, 2017

-

October 2017

- Oct 30, 2017 NPC Job System Oct 30, 2017

-

September 2017

- Sep 1, 2017 Resources and Resource Systems Sep 1, 2017

-

August 2017

- Aug 3, 2017 State of the Game - Episode 1 Aug 3, 2017

-

June 2017

- Jun 20, 2017 Resources: Processing, Consumption and Inventory Jun 20, 2017

- Jun 15, 2017 Energy is Everything Jun 15, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 16, 2017 Graphing Script - It's not exciting, but it needed to be made May 16, 2017

- May 2, 2017 Tutorials: Low Poly Snow Shader May 2, 2017

-

April 2017

- Apr 28, 2017 Low Poly Snow Shader Apr 28, 2017

- Apr 21, 2017 Environmental Simulation Part 2 Apr 21, 2017

- Apr 11, 2017 Environmental Simulation Part 1 Apr 11, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 24, 2017 Building a Farming Game Loop and Troubles with Ground Water Mar 24, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 25, 2017 The Inevitable : FTF PostMortem Feb 25, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 7, 2016 Leaving Early Access Dec 7, 2016

-

November 2016

- Nov 28, 2016 Low Poly Renders Nov 28, 2016

- Nov 1, 2016 FTF: Testing New Features Nov 1, 2016

-

October 2016

- Oct 27, 2016 Watchtowers - Predictive Targeting Oct 27, 2016

- Oct 21, 2016 Click to Color Oct 21, 2016

- Oct 19, 2016 Unity Object Swapper Oct 19, 2016

-

September 2016

- Sep 18, 2016 Testing Single Player Combat Sep 18, 2016

-

May 2016

- May 25, 2016 Release Date and First Video Review May 25, 2016

-

March 2016

- Mar 26, 2016 Getting Greenlit on Steam Mar 26, 2016